When Malala Yousafzai was shot at age 15 on her school bus in Pakistan, the world cried for the teenager the Taliban tried to stop from going to school. Instead of instilling fear in her, the harrowing 2012 ordeal gave the young activist the courage to set out on a mission to ensure that every child in the world has an education.

A year later, she received the most prestigious European human rights prize, the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, following past recipients like South Africa’s Nelson Mandela. In 2014, Yousafzai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize—she was the youngest recipient in history—for her worldwide campaigning efforts for girls’ education and rights. After that came the movie He Named Me Malala, chronicling Yousafzai’s life.

Her strong sense of God as love, family, and the universal power of healing comes through in this impactful sit-down, here, with Oprah Winfrey. It’s a Father’s Day tribute, too, to the man who raised his daughter with respect, and who joins her in the discussion. Yousafzai’s recent trip to Pakistan for the first time since the shooting has kept her honorable efforts in the spotlight, with the world still conspiring to further her mission.

OPRAH: Is there a part of you that believes that you are, first of all, more connected to humanity in a way that you weren’t before the attack, but that so much of your life belongs to the world? Do you feel that?

MALALA: I have gone through these experiences of being deprived of education, and seeing terrorism, seeing schools being blown up. It helps you to know how other people feel when they go through the same circumstances in their lives, when they suffer through the same difficulties. So now, seeing around the world that children cannot get an education, and girls are facing so many difficulties and they are deprived of independence and being themselves, it reminds me of my past, and then I think that with what I have gone through, I should now help people not to go through the same situation of terrorism.

OPRAH: So when you were giving your Nobel Peace Prize speech at 17—first of all, how do you even begin to write a Nobel Peace Prize speech? How did you begin to frame that, what you wanted to say to the world?

MALALA: Well, just a week or two before the speech, I had my exams. So I was totally focused on exams. I couldn’t give five minutes to the speech. And I said, I need to do well in my exams. So I was just totally focused on my work.

OPRAH: For high school still.

MALALA: Yes.

OPRAH: You’re the only Nobel Peace Prize winner who had to also focus on their exams.

MALALA: But I really wanted this speech to be the voice of girls, to be the voice of children. And it was wonderful because we invited five girls from Nigeria, Syria, and three girls from Pakistan, including the two girls who were attacked [on that school bus with me]. And all these girls had a story. They represented girls in Nigeria who were abducted by Boko Haram, or girls in Pakistan who suffer from sexual violence, or Syrian girls who are now refugees. They had a story, and that made my day very special, to feel that I was not just one girl but I was many. I was speaking on behalf of those millions of girls who are deprived of education, and that really made the award more precious to me. It felt like I was receiving it for the children.

OPRAH: When extraordinary things happen, they often begin with ordinary days. There had already been announcements by the Taliban that girls were not supposed to go to school, and girls were not supposed to go to the marketplace in Swat, where you lived. Yet you were still doing it. Were you afraid?

MALALA: Well, that was a very difficult time. More than 400 schools were destroyed. And women were not allowed to go to markets. And girls’ education was banned completely. And I was not really afraid of speaking out, but I was afraid to live in that situation. I did not want to live in a situation where I had no freedom, where I did not have the right to be who I wanted. And the next thought that would come to my mind was, am I going to be just like the other women in my community? Getting married at a very early age, 13, 14, and then having children, and then grandchildren, and that’s it. That will be my life. I wouldn’t be myself.

OPRAH: You thought, if I don’t get an education, I’m gonna end up like all these other women.

MALALA: Yes. And this is what I feared the most. Rather than fearing that if I speak out, I will be targeted.

OPRAH: So you were willing to be targeted, even knowing that speaking out you could lose your life. But you didn’t think it was possible. because at that point, the Taliban had never harmed children. Right?

MALALA: Yes, you are right. And, they are the most brutal people, terrorists, and they have done things which have shocked people. But no one could imagine they would target children. They have destroyed schools, but they never killed a child, targeted a child who spoke out. And so it was very unusual. And I always used to think about my father, because we both used to speak together about this campaign of education and I would speak on behalf of girls, and he would speak in support of schools, women’s rights, peace and girls’ rights. So I was really worried about my father, that he might be targeted. I used to think, what should I do if someone comes to our house? My mother had put a ladder at the back of the house, so if someone came we would tell my father to go very quickly out the back. And my mother even decided to put a knife under her pillow. But then she said it’s too violent. She wouldn’t do that. And I always used to think about that: How can I protect my father?

OPRAH: You described how you were on the bus, sitting there with your friend. Someone stopped the bus and came aboard, but you didn’t immediately think they were there for you. Do you remember the feeling of being shot?

MALALA: I don’t remember that incident at all. I just remember I was talking to my friend and thinking about the next day. We had exams at that time. My exam went very well on that day. I was thinking of the next day’s exam. So I was quite happy in that moment. And then suddenly I’m waking up in Birmingham [England] in a hospital, seeing doctors and nurses and having no idea what had happened in between.

OPRAH: So when the terrorist enters the bus and asks, Who is Malala? Where is Malala?—what did you think?

MALALA: I do not remember. But my best friend, Moniba, says when the person came and he asked, Who is Malala?, some of the girls looked at me because they had no idea what was going to happen next. Later, I asked her, What did I do? How did I react? Was I scared? And she told me, You said nothing, but you were holding my hand so tightly that I could feel pain on my hand.

OPRAH: Mm.

MALALA: And then she said as he fired bullets, I fell down into her lap and started bleeding. And then they fired two, three more bullets and—my other two friends were hit as well.

OPRAH: And when you awakened from the coma, I heard that the first thing that you asked was, where’s your father?

MALALA: Yes. Because I thought he got attacked and I was very worried about him. I first thanked God that I was alive. It’s a very difficult moment when you want to wake up and prove that you are not dead. When I woke up, I said, yes, I am alive. And I’m existing. And I haven’t gone from this world yet. Then I asked, where’s my father? It was a very difficult time—I could not speak, because there was a tube in my neck, and I really wanted to ask many, many questions. And I would try to write them to ask the doctors. But then 10 days later, when I saw my family, that was the first time that I cried. It was a very emotional moment to see my family again.

OPRAH: Tell me, in what way did your near-death and the world’s outcry, prayers, candles lit around the world, in what way did that experience deepen the meaning of your life?

MALALA: When I was in the hospital, I had no idea that people outside had so much support for me, and they were praying for me and sending cards and letters. But the doctors and the hospital staff would bring cards to my room every day. It totally surprised me. I believed in prayers before, but this strengthened my belief in prayers—that the prayers of people are so powerful that that can give you life and that God listens to them.

OPRAH: I know you believe there are two reasons your story is unique. Prayer and love. You could feel the love and outpouring from people, could you not?

MALALA: Yes. I think there was nothing greater than the love and the prayer of people. It’s so special. You can’t buy it.

OPRAH: No.

MALALA: It’s a gift of God.

OPRAH: You have been called the bravest girl in the world. “Now meet the bravest girl in the world.” What does your heart say when you hear those words?

MALALA: People think I did a brave thing, that I spoke out for education, and then even after I was attacked I spoke out again. So it’s defined as bravery. For me, bravery is when you speak up for what is right. And it’s our responsibility. It’s not something extra, that we’re doing a favor to our community. I think it’s our duty to speak out for what is right.

OPRAH: And where do you think you started to embody that? We see in the wonderful film, He Named Me Malala, that from a little toddler you’re crawling around in the classrooms and you’re listening to your father teach. So obviously the way you were raised had a lot to do with how you felt about yourself.

MALALA: Yes.

OPRAH: And the strength that you hold for yourself as a young girl and a growing woman. But where does that come from? Because the thing that you say at the end of the movie is so powerful. I’m not going to give that away. But what you say, you worked to become this girl.

MALALA: Yes. But who really inspired me was my father. And my mother, of course. I went out and listened to my father speaking out for education and for women’s rights. It really inspired me. Sometimes we think that the person who will bring the change will be very special and he would be like Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela, that they can’t be among us. And we don’t realize that they are just normal people like us.

OPRAH: Like Malala.

MALALA: Well, I haven’t done that much yet. And it’s my dream to be like them—the change that they have brought in society, that I can do the same. But it’s the beginning of the journey, and it began with a small step. It’s helping the community. If you truly have that ambition, once you start it, if you have a strong commitment, then you can do it.

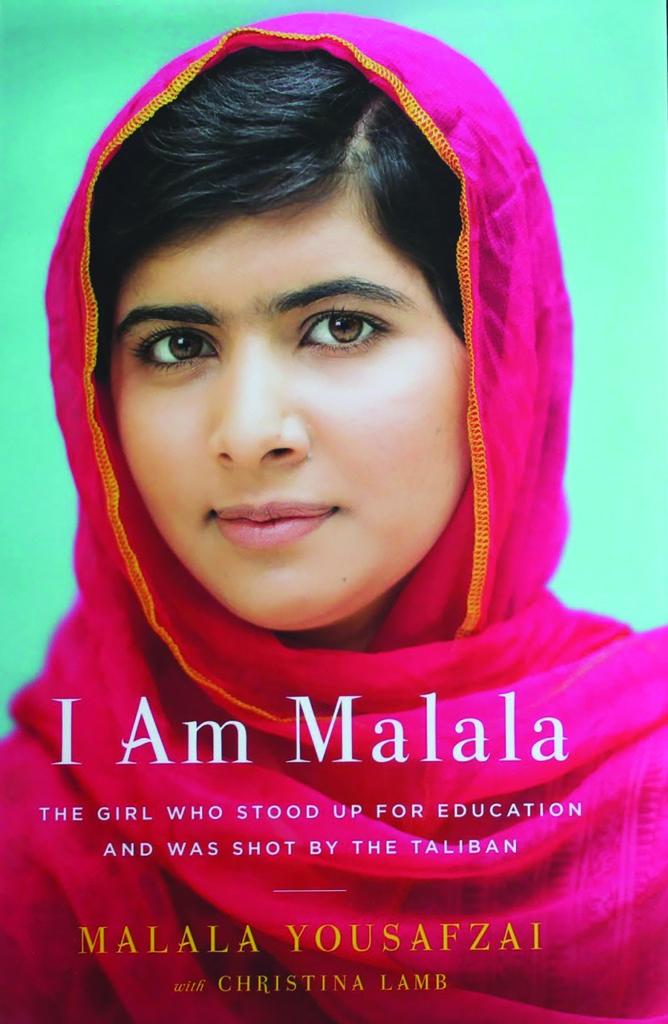

OPRAH: Your journey is featured in a documentary by Oscar-winning filmmaker Davis Guggenheim called He Named Me Malala. You’ve also written a best-selling memoir called I Am Malala. I love where you say, “I know God stopped me from going to the grave. It feels like this life is a second life. People prayed to God to spare me, and I was spared for a reason, to use my life for helping people.” Do you believe that?

MALALA: Yes. I strongly believe that. I believe that this life is purely for a purpose and that is helping people. That is, doing something for the world and doing something for the betterment of this society and for girls. And—this is a second life, a new life, yes.

OPRAH: You say, “When people talk about the way I was shot and what happened, I think it’s the story of Malala, a girl shot by the Taliban. I don’t feel it’s a story about me at all.” Does it really feel kind of separate from you sometimes?

MALALA: I think one reason for this is, I don’t remember the incident. So it does not make me feel like I was the girl who was shot. She was just Malala, the girl who was shot by the Taliban. She has got this definition. She’s now someone else for me. For me, I am this person with a heart who strongly believes that doing something for your people is important and you should do—as much as you can.

OPRAH: You say that you’ve never been angry at the men who shot you. Never. Not a moment?

MALALA: Well, I think that in order to go forward, it’s important that you have love in your heart. And I want to have love in my heart. I don’t want to have any hate, any bad feelings in my heart. And that’s what makes me more happy.

OPRAH: So you never had a “why me” moment?

MALALA: No. Because I believe that whatever happened, bad or good, it’s really important to focus on the future and learn from your past. In order to go forward, you have to focus on your future. And if every day for the last three years, I would have cried, why it was me, why it was me, nothing would have been done.

But instead of saying that, I said, OK, even though I was shot, I’m not the only girl who has been a victim of discrimination in society, or being attacked in terrorism or gotten deprived of education. There are millions of girls. And the best way to fight against terrorism is to educate girls, to empower them, to raise their voices. And in those last three years, I made a trip to Jordan to speak out for Syrian refugees, and to Lebanon and Nigeria, and this is the best revenge you can ever take.

OPRAH: Tell me how you celebrated your 18th birthday.

MALALA: I went to Lebanon and Jordan, and we opened a school. And that is the greatest thing you can ever do. You see girls in their school uniforms sitting with books, sitting in the classrooms. What else can you do better than this? You changed a girl’s life. You gave her books.

OPRAH: From a school you built. Yes.

MALALA: Yes. So that was the most precious gift I’ve ever received—the love of those children.

OPRAH: Pretty cool. I think it’s wonderful. I was, what, I don’t know, I was 50 when I built a school, not 18. But when you have won the Nobel Peace Prize at 17, and you’re building schools around the world, and there’s the Malala Fund [malala.org] to which anybody can donate, that’s what you want to do. You want to create educational opportunities for 66 million girls in the world who don’t have it. Do you do normal 18-year-old stuff?

MALALA: Well, I do have lots of friends now and we go out shopping and go to restaurants, enjoy my time. I also like playing cricket and badminton—and fighting with my brothers.

OPRAH: Fighting with your brothers.

MALALA: I really enjoy it.

OPRAH: So this is what’s interesting: Living your truth nearly cost you your life. You’ve said if you’re afraid, you can’t move forward. Is courage something that you think other people can develop or give to themselves? This belief system that allowed you to stand up for what you believe was the right thing for girls to be able to go to school. Are other people able to have that?

MALALA: Well, there’s this fight between courage and fear. Sometimes we choose fear, because we want to protect ourselves. But we don’t realize that by choosing fear, we put ourselves in a situation that has a really bad impact.

If I would have kept silent in Swat Valley and my father would have kept silent and all of us would have kept silent, then there would not have been that moment when change would have come to us in our valley.

So it’s better to speak out, to have that moment when you say, I’m going to do something for my side. And that needs a bit of courage. Our courage was stronger than our fear. There was fear, it wasn’t that we just totally were fine with what was going on in our society—we were afraid. The fear that I would be away from school really motivated me to have the courage to speak out.

OPRAH: What does it mean to you to be a Muslim woman?

MALALA: For me, being Muslim means to be peaceful, to be kind, to always think about others, and to always think that how the one action you take can affect other people’s lives.

OPRAH: So you feel a responsibility to embody what you believe to be the characteristics of Islam?

MALALA: Yes.

OPRAH: And that is peace.

MALALA: Peace.

OPRAH: And love. You’ve said that the people who did this to you were not about faith, they were about power. And I think that for so many people in the world, that power and that terrorism and that way of looking at life is what they see of Islam. What do you want to say about what Islam is? What do you want people to know about Islam?

MALALA: As far as I know the word Islam means peace. It’s a religion of brotherhood, humanity, kindness and generosity. And what I have learned is that you have to be kind to each other. You have to respect each other’s religious beliefs and culture beliefs. I don’t understand the Islam that the terrorists are showing, that is killing people.

OPRAH: And even in your family when this happened, there was a time where your mother was saying, well, they’re not Islam. They cannot be.

MALALA: Yes. And when I was attacked, my mother was worried about me, but she also thought about the mother of the person who shot me because she thought, how would that mother feel, whose son just shot three girls in a school van?

OPRAH: Do you fear the Taliban still?

MALALA: No. Why should I? When you go through the situation, that you are attacked and you are nearly killed, and after that you survive and you are alive and you’re still speaking out, then there’s nothing else you should be afraid of. Like, what else can they do? They can only kill me. And it didn’t work. So it means nothing else can work. And this movement is still alive. This movement that girls deserve education, this campaign, this voice, it’s still alive. They can’t kill it.

OPRAH: And even if they do kill you?

MALALA: They can’t stop the movement. This is what I want to survive. Not me. But the movement.

OPRAH: Has this experience made you less afraid of death?

MALALA: Yes. Definitely. Before the attack, I used to think, how would it feel if I were attacked? I sometimes did think that I would be attacked. But after I was attacked, as I said in my U.N. speech, I realized they changed nothing in my life except that weakness, fear and hopelessness died and strength, power and courage was born. I feel stronger than before.

OPRAH: Your father and mother raised some kind of woman child!

MALALA: Thank you.

OPRAH: I’ve met your father. He’s an extraordinary man. What do you want to say about him before he joins the conversation? Because it’s hard when you’re sitting next to the person to say the things you feel sometimes. I could weep thinking about your father. Because obviously I know that there is nature, you’re born a certain way, and then there’s nurturing and support. But I marvel at the kind of vision and foresight your father had to allow you to be a girl who could grow in her own truth, and to allow that in a culture that said nobody else is doing that. I mean, your father may be the bravest person I’ve ever seen.

MALALA: About my father, I can say that he let me to be who I wanted. He did not stop me. And if he would have become the typical father who stopped their daughters, not to go to school, not to be independent, not to have a say, not to have the right to speak, I wouldn’t have become who I am today. My father never, ever, stopped me from having a say and from saying that I, too, have an opinion. Even when I was 8, 9, 10, 11. He said, Yes, your view matters. And you should give your ideas. And he would appreciate it. He would say, Oh, well done. Amazing.

OPRAH: And that is not true of all women in your culture.

MALALA: Yes.

OPRAH (to Malala’s father, Ziauddin Yousafzai): We were complimenting you. I think you share that Nobel Peace Prize in a way because to be able to raise a daughter who could live her truth the way your daughter does, is so exemplary, and speaks to you and your wife. We see in the movie—it’s a precious moment in He Named Me Malala, when you’re brought the scrolls of your family tree, and there is not one female’s name on the generations. You look at it and say, “I’m going to put my daughter’s name. Malala.” Why did you do that?

ZIAUDDIN: In patriarchal society, usually women are associated only with men. Mr. So and So’s daughter. Mr. So and So’s mother. Even if you take a woman to the doctor and the doctor asks, what’s this lady’s name? And the man says, just write Mr. So and So’s wife. For me, it was unacceptable. Malala had a name.

OPRAH: And were you doing that in defiance of the culture?

ZIAUDDIN: Yes, of course. I mean, I can’t say that in patriarchal societies fathers don’t love their daughters. But how do you manifest your love. Is your love only controlling your daughters? Is your love only to make them like slaves, that you say that I am controlling your honor and chastity, so I’m keeping you in four walls. I’m not educating you, because it is my idea of love? For me, love was something different. Because of my education, the way I was groomed, I learned that love means freedom. Love means respect. Love means independence. And that made my treatment and my mindset and my behavior different toward my daughter.

OPRAH: One of the things that struck me the most in He Named Me Malala, is you said she was not shot by a person, but by an ideology. What did you mean by that?

ZIAUDDIN: That’s a very important question. The way some of the terrorists take Islam is the way they define it. I mean, if you ask the guys who attacked her, they don’t know. They have been just told that, somebody told him that this girl, she is campaigning for Western education, then she should be killed.

OPRAH: So she’s forgiven them. She never had any anger. You didn’t have any anger either?

ZIAUDDIN: Of course. I mean, I have an anger because of the power seekers who have defamed and distorted the true religion of Islam. I have anger.

OPRAH: About that.

ZIAUDDIN: About that. And I feel pity on the youth and on the young men who have been recruited for this horrible job. They don’t know better. They have been completely brainwashed, like robots. I feel pity for the boys who did that.

OPRAH: Malala, finish this sentence. I believe...

MALALA: I believe and I know for sure that if you have strong commitment within your heart, if you have love in your heart, that you want to do something better, the whole world and the whole universe supports you and your cause. I had this simple one-sentence dream that was to see every child going to school. And I spoke out for it and my father spoke out for it in this small valley in Pakistan, Swat Valley, and the journey started, and now it’s going on and getting better and developing each and every day.

OPRAH: What do you believe about love?

MALALA: Love is the greatest thing on Earth. What’s more beautiful than love? The love of your parents, the love of your brothers, and after that day, what I received was the love of people. That really strengthened me. If I wouldn’t have received it, I might not have been able to go forward.

Courtesy of Harpo, Inc./Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations, which are available on Apple Podcasts: ApplePodcasts.com/OprahSuperSoul