As dedicated modernists, Barnes Coy Architects have been obsessively engaged with the more subtle nuances of design: the way a corner meets, the texture of stone, the reflectivity of a glass-curtain wall—just the kind of elements that are often overlooked, but make the difference between an everyday experience of architecture versus a kind of spatial poetry. No two of the firm’s houses are alike; each is custom-tailored to the client’s needs and dreams. For Christopher Coy, founding partner of Barnes Coy Architects, the commitment to pure design has become something close to a religious calling.

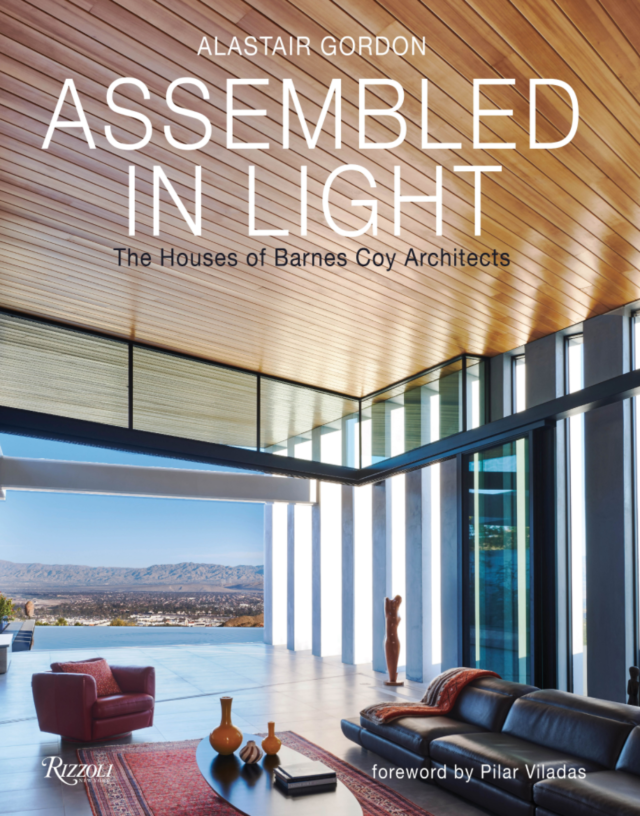

Coy grew up summering in the Hamptons and had a passion for mechanical devices, airplanes, motorcycles and James Bond movies. In his preface to Assembled in Light, the new monograph published by Rizzoli and Gordon de Vries Studio, he writes: “Designing a house is the front line of modernism…. It becomes a catalyst for self-discovery and personal transformation.” Over the 25-year span of their partnership, Coy and Robert Barnes stayed true to a modern vocabulary of minimal forms, flat roofs, revealed structure, wildly intersecting geometries, skylights and floor-to-ceiling transparency, so that interiors are saturated with natural light. The title of the book, Assembled in Light, refers to Le Corbusier’s quote about architecture as a “magnificent play of volumes assembled in light.”

Barnes Coy believes that architecture begins with the site; all of its houses are site-specific insofar as the essential forms are generated by the surrounding environment. The shape of an oceanfront house in Water Mill, for instance, was prescribed by environmental setback lines from the ocean on one side and a freshwater pond on the other. The curve of the house’s north façade follows almost exactly the wetlands setback, while the south façade echoes FEMA’s coastal flood line. With one of their more recent houses, the architects broke up what might have been a fairly massive, monolithic volume into smaller parts, resembling three beach houses, so the scale and natural rhythms of the oceanfront site were not overwhelmed by the building. It’s all about interpretation of setting and natural context, as exemplified by the acrobatic engineering they invented for a steep jungle site in Costa Rica that overlooks the Pacific Ocean. The crescent shape of the house is pierced by a long, elevated walkway that points toward the setting sun. In a completely different setting, the architects designed a house for the tidal swamps of southeast Georgia by lifting the main structure high above the floodplain on giant cypress logs that were harvested from a nearby marsh.

Assembled in Light: The Houses of Barnes Coy Architects, written by Alastair Gordon with a preface by Pilar Viladas, principal photography by Michael Mundy, and designed by Barbara de Vries, is co-published by Rizzoli and Gordon de Vries Studio in September 2020. barnescoy.com