By Ray Rogers

Renée Cox cuts an impressive figure. The day we meet at Guild Hall, she sports a body-hugging, fringed green camouflage dress, Rasta-colored manicured nails, and her voluminous amber curls crown her striking angular visage. This bold ethos extends to her head-turning artistry, seen in a wonderfully curated overview on display in A Proof of Being at Guild Hall through September 4.

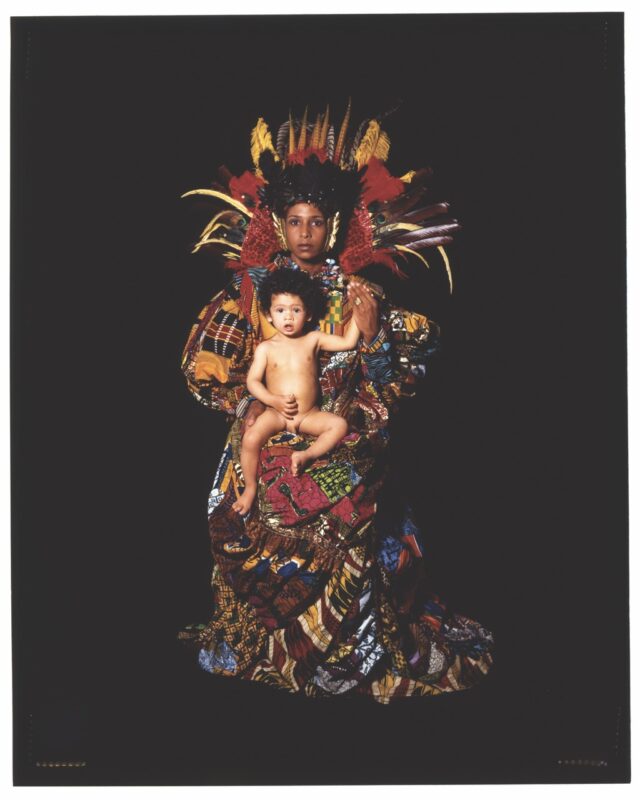

In Cox’s photographic works, often recreations and reimaginings of religious and historical portraits, the artist is resolutely front and center, her direct gaze demanding the viewer’s attention. At first look, these daring pieces are visually stunning. Linger longer, and you’ll find multilayered meaning in works that have wowed, shocked and awed audiences for three decades. In 2001, then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani even went to war with—and lost to—the Brooklyn Museum over Cox’s “Yo Mama’s Last Supper,” wherein the artist placed her naked self in the role of Jesus Christ in a work that referenced Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” painting.

A longtime resident of East Hampton, she was a natural choice to be the first artist to show at Guild Hall after the historic cultural center’s first major refresh; its new modern feel and clean lines brilliantly showcase Cox’s visual masterpieces, old and new.

Ray Rogers: Your career began in editorial, shooting fashion stories. Did you always know you had something more to say and do with your talents?

Renée Cox: Yes, and I also knew that after I had my first child that I wanted to have my work be a legacy I could live off. Shooting editorial, my work only had a 28-day life span. The pivotal moment for me was being at Jerry’s, a Soho restaurant, with a whole crew of folks, some very well-known photographers and the Macy’s crew, because I used to do their full-page fashion advertisements. At one point I say, “God, today is a special day. Nelson Mandela got released from prison.” Like after being in prison for over 27 years. There was a pause and then they said, “But Donald and Ivana [Trump] are getting a divorce.” In that moment, I knew I had to leave fashion. I knew I had to go back to school and get my credentials. I went to the School of Visual Arts, got my master’s degree and then enrolled in the Whitney Independent Study Program.

RR: Was there a flash where you thought, yes, I’m on the right path?

RC: Oh, yeah. It was at the Whitney Program. I was the first woman in their 25-year existence to be pregnant. I was having my second child, and told them I was pregnant and everybody looked at me like, “Oh no, what are you going to do?” I’m like, “Wait! This second kid has been planned.” When they asked what would happen to my career, I had no idea what they were talking about. I came from fashion, I had my first kid, I was working and people were like, just don’t break your water on our shoot. My nanny came to the shoot with the baby and I would go into another room and breastfeed. No big deal. And now here I am in this supposedly more intellectual world and they don’t understand babies?

RR: Or motherhood.

RC: Don’t you people have mothers? Is this supposed to be the Immaculate Conception? That’s when I realized, OK, I’ve got to comment on this. I’m going to do “Yo Mama” and show them that you can have a kid and put on your stilettos and have a good body line. I’m not giving you sensible shoes making me look like a peasant. Feminists embraced the image—she’s holding her kid like an Uzi! You can make your own judgments. But no, I’m holding my kid like this is how you move a kid really quickly.

RR: What prompted your desire for representation?

RC: I did not like the way we were represented because it was usually in a derogatory manner. So when I started I felt I had to flip that script and create uplifting, empowering imagery that showed Black people as I know Black people.

RR: Black motherhood is also a powerful theme in many of your works, such as “Yo Mama’s Pieta,” which is still viscerally relevant today. The police brutality and killing of Black people only seems to have gotten worse, or maybe more accurately it’s just more visible.

RC: Absolutely. It’s more visible. It’s been going on for the last 400 years. In essence, the police are descended from the slave catchers. Every week we hear of some young Black male who was shot down someplace. That’s why “Pieta” is still relevant, which is sad.

RR: Tell me about the creation of your superhero, Rajé. I love the piece where she’s freeing Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben off the box labels.

RC: For me it was a very simple question—who owns Uncle Ben and Aunt Jemima? And it doesn’t take much to find out that white people owned it. Why are we still on their boxes? When you start going back into the history, it comes down to this thing of house Negroes basically. They were the ones who were desexualized and lived up at the big house; everybody loved them. They might have been a wet nurse for these slave masters’ children. And it’s very interesting that white folks take comfort in that. It’s like yeah, we have some big fat Black mama up in your kitchen here and she’s cooking up some good pancakes. Really? And Uncle Ben, a similar story but another little irony with Uncle Ben is you wouldn’t have rice here if it wasn’t for the African slaves that they brought over, because they introduced rice here in the U.S. That’s another layer to the story.

RR: If you’re curious to know more history, you’re giving people a window, a portal to explore. I’ve heard you talk about your search for some Power Rangers toys for your kids, and how that inspired the work.

RC: Yeah. I was in a Toys R Us and it was Christmastime and my kids wanted Power Rangers, so I’m there basically playing football with people trying to grab these Power Rangers and in the process of doing that I look around and I go wait a minute, I don’t see any Black superheroes. Why is that? OK, let me create one. Then I researched Wonder Woman’s history and found that the creator of Wonder Woman had in the 1970s a Black Wonder Woman named Nubia, back when Black was beautiful and you had Ultra Sheen ads on the side of buses saying that. I say my character is like the granddaughter of Nubia and her name is Rajé. Initially her name was Rage, but I changed it because I was like if I say Rage people are going to disregard it and just say I’m an angry Black woman.

RR: Is that stereotype or trope of the angry Black woman something that you find you are accused of or something you have to fight against?

RC: Not a lot, but I definitely can be accused of it because I do work which is thought-provoking and empowering. Because the work is challenging, as some people would say, you get that a little bit.

RR: This is a good segue into the Giuliani war over “Yo Mama’s Last Supper,” the piece shown at the Brooklyn Museum. I read that the outrage added up to near-record numbers at the time for visitors at the museum.

RC: Good for the museum, but I will say publicly the museum at that time did not give me one iota of help. They threw me to the wolves because people think that normally the artist is going to cow down and become like a puddle of water in a corner and not really deal with it. I was alone. Chris Ofili [the artist whom Giuliani went after a few years prior, for his elephant dung-embellished mixed-media painting “The Holy Virgin Mary”] had Saatchi and galleries to speak on his behalf. I didn’t have anybody to speak on my behalf and I had zero respect for Giuliani as it was. With his “stop and frisk” and all of these other stupid policies that he had going on, and I really found his comb-over revolting. And also the fact that he had his wife Donna Hanover crying all over the TV when they were getting a divorce.

When they asked me, I was at the Brooklyn Museum, with my NYU students. I was teaching at the time, and they were all white, so I felt a personal responsibility to bring them to see this show called Committed to the Image, which was works by 96 Black photographers. If I don’t show it off, who is going to show it off? Fortunately, I got through 75 percent of the show and then we came to my work and it was roped off, like it was Studio 54. Sometimes when I have work in museums I’ll go up and touch it and then everybody says you can’t. Then I’m like, “No, I can. It’s mine.” I did that there and it was like a Fellini movie: All of a sudden, all these press people popped out of the woodwork. I had microphones in my face within seconds. It was crazy. “Mayor Giuliani says that you’re anti-Catholic.” At that time I will admit I was a bit in my ego mind so basically I turned away from them and I said to myself oh my god, I’ve been waiting for this level of attention all my life. I turned around and I was basically like, “What did he say about me? I’m anti-Catholic? What about him? What about commandment No. 7 I believe it is. Thou shalt not commit adultery and he had his wife crying all over Fox.” That was the beginning of it and they ran with it. The next day I was on the cover of the Daily News. I had fun. I was not shutting up.

RR: How does it feel to be celebrated here at this important cultural institution in the Hamptons, where you and your family have had a home for many decades?

RC: I’m very happy. This space that has been dramatically changed from what it once was is a great showcase for the monumentality of my work. There’s total harmony. I feel like it’s a marriage of image and architecture. It just flows.

We’ve been here since ’89. I even went to a boarding school in North Haven called Tuller Maycroft when I was 11 or 12. And before we even had a house, in the early ’80s a bunch of friends and I would go out to Napeague and set up tents on the dunes. My million-dollar view! Back then you could do that. I’ve always had a love for the geographical presence of this area. There’s still open space but I also like being close to the sea, so upstate New York doesn’t really do it for me. I feel crunched in.

RR: This work in front of us, “Cousins at Pussy’s Pond,” was shot in East Hampton in 2001. In what way does the landscape of the area inspire you?

RC: It goes hand in hand. This is from my American Family series. I knew I wanted to do my flipping of the script. It’s playing with the impressionists’ images. [Édouard Manet’s “The Luncheon on the Grass”] was done on one of the little isles in Paris. I did some research and found out that Manet took the composition from a third-century Roman sarcophagus called The River Gods. So I did mine with this notion of the river gods, and shot it in Springs at Pussy’s Pond.

RR: There is also new work in this show, the sacred geometry pieces in “Soul Culture.”

RC: I wanted to create another universe that Black and brown people could thrive in. There are even some white bodies in there, too, but I wanted that to be our place within the universe or the dimensions. Right now we’re in the third dimension but there are actually 12 dimensions in total. I was like, let’s create another space, another world where people of color can thrive.

RR: And their bodies are celebrated.

RC: Exactly. They’re not enslaved and they’re not being massacred or brutalized. And we’re in control. One of the big points for me, too, is controlling the gaze and that’s why all of these images they’re all looking right back at you. People have said, Oh, you’re like a Cindy Sherman. I’m like no, because Cindy doesn’t return the gaze. She’s not direct, and for me I feel it’s necessary to be direct. It’s like yeah, you can look at my body but I’m also looking back at you, too. I’m not letting you off the hook.

RR: What enlivens you about your role as a professor at Yale, and what excites you or gives you hope about new generations of artists that you mentor?

RC: It’s fun. I like young people and I think they relate to me, too. I’m always telling them to stop second-guessing yourself. Stop comparing yourself to this one, that one. Do what you feel. I also try to give them that little self-love that they should have and to build their confidence. I don’t think you should be afraid to say ‘No, I’m fucking good.’ It’s like I’ve said: I’m not waiting for anybody to validate me, I validate myself.