By Ray Rogers

In one landmark work after the next, Bill T. Jones has cemented his reputation as a pivotal force in modern dance. A dynamic storyteller who rails against convention, Jones tackles issues of identity, race, sexuality, faith and, ultimately, what it means to be human. He made his mark with works such as Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land—his sprawling 1990 flashpoint that reimagined Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel as a starting point and culminated with nearly 70 naked dancers on stage—and the epic 1994 Still/Here, an unforgettable piece about living with HIV and surviving the AIDS crisis.

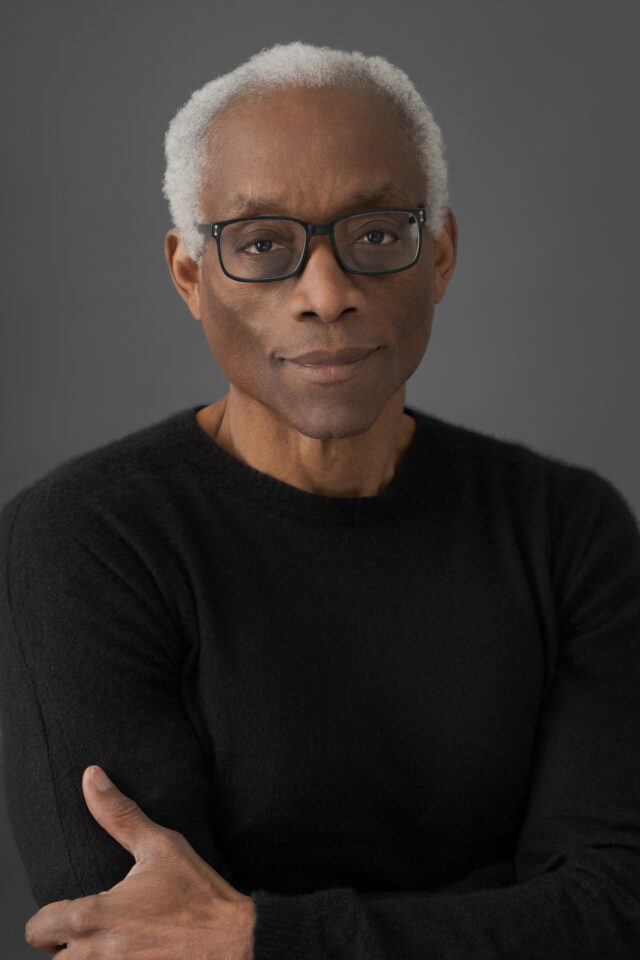

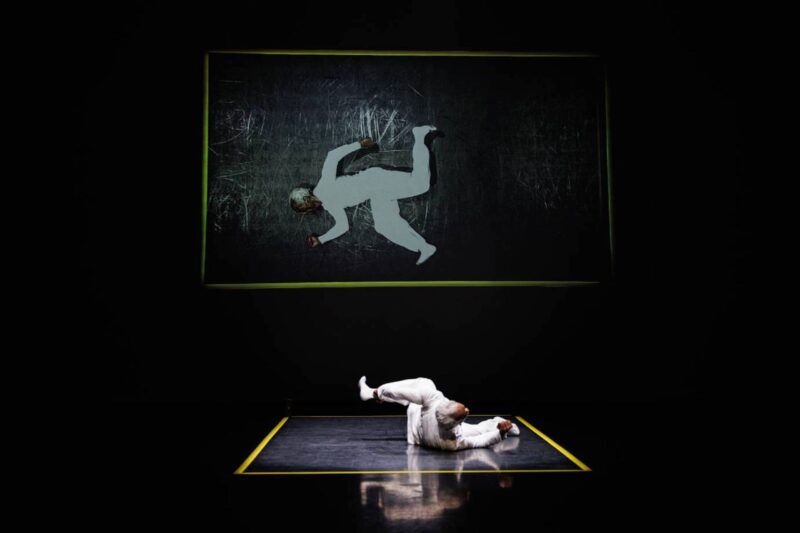

The Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, which he formed in 1982 with his late partner, who died of AIDS-related lymphoma six years later, takes a multimedia approach, employing text, sound and video installations to heighten Jones’s powerful, cerebral works, all performed by a multiracial troupe of dancers of varying shapes and sizes that prizes the full range of the human experience. Purist spoke with the 1994 MacArthur “genius grant” winner and 2010 Tony-winning choreographer (for the jukebox musical FELA!, about the life of the acclaimed Nigerian afrobeat singer and activist Fela Kuti) about his vision for his August 15 date at Guild Hall, and the power of storytelling and resilience in the face of adversity.

PURIST: We’re living through unprecedented times politically. Your recent work, Curriculum III: People, Places & Things, staged at New York Live Arts Theater in Manhattan this May, fully meets this terrifying moment in America. I’d like to hear about your inspiration for the work, the third in a cycle, and the message you’re delivering.

Bill T. Jones: Curriculum III was informed in some ways by the plight of the citizens escaping Syria trying to get to Italy, and the boat was on the high seas for an obscenely long period of time being shuttled and denied port of entry until it capsized and hundreds of people died in a horrible way. That was just one of many stories of people who were literally dying for a better world. Dying to come to Europe or dying to get here.

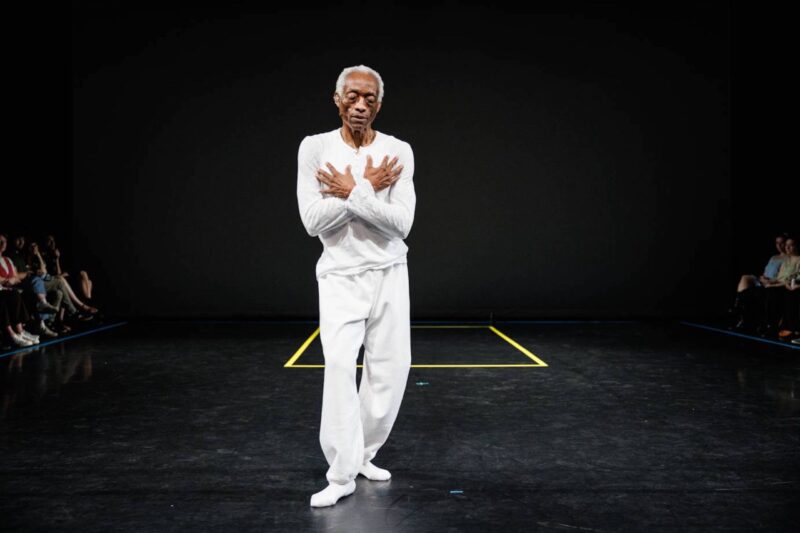

My dancers and I worked on it for about three years. I decided that I didn’t think we had the right to be taking on someone else’s plight when we had not owned our own relationship to the question of who belongs where. Who are we? The prompt for all of my dancers was: Are you an American? Could you tell me your family’s mythology or history? It was a company team-building exercise for me. We don’t call the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company a dance company—we call it an ensemble that’s able to deal with text, music and movement with high levels of accomplishment. That is how People, Places & Things found its voice, through the dancers telling their own histories. This is something I’ve been doing for years in my own work, but now it’s great to see a generation of performers who are eager and willing to do that. That’s what People, Places & Things was: What makes you an American in this particular moment when we’re being told that some people should be here and other people should not.

Tell me about the piece that will be at Guild Hall, a version of Story/Time, one of your iconic works, which was inspired by John Cage’s Indeterminacy.

It’s an event that I am fashioning. It is a hybrid version of Story/Time informed by that John Cage piece. He told 90 stories in 90 minutes; I did 70 stories in 70 minutes. Cage was looking at the Cold War, and the state of the world in the 1960s and ’70s, asking himself whether his art was relevant. In his study of Eastern philosophy an important teacher said to him, John, you don’t have to have all of the answers. He needed another way, so he began to use indeterminate means, like to throw coins or dice to determine sequence. I took this as a kind of privilege of a white man that he was able to do something so audacious like that. I said, what would happen if I were to write and collate my own stories? I wrote my stories coming from my position as an African American person, and a gay man and the things that preoccupy me, such as death, of course. So, I wrote a whole bunch of stories and I put them together, juxtaposed, as Merce [Cunningham] did, with materials, dance phrases and all that were through chance procedure, organized in time and in space. That’s what Story/Time was.

How will the work at Guild Hall vary from this form?

Guild Hall is a wonderful opportunity to do something experimental and intimate, and something that is very much on my mind now. I recently gave an address at the Summit Conference in Detroit called I Feel the Earth Move Under My Feet. This was a work that was informed by how pissed off I am at the new Trump administration. That Carole King song with its poppy title spoke of the way that I felt having grown up, born in 1952, with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the Civil Rights struggle, “Free at Last, Free at Last,” the gay liberation struggle. All of those beliefs I had, it seems like a retrenchment now and I was thinking it was like the world was moving under my feet. I made an address trying to invite the audience in to hear my thinking and feeling through the stories that I’m telling.

I saw one of the Story/Time performances from years ago and was just transfixed. There was so much joy—and also so much terror in many of the things that you’ve experienced in your life, in terms of the homophobia and racism and encounters with police officers. But also, incredible anecdotes about so many towering figures of culture, like Cecil Taylor, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Merce Cunningham.

I like trying to organize, and artmaking is participation in the world of ideas—that’s one of my favorite slogans. Another is: “Art happens when something is being pushed against.” One thing that’s always being pushed against are the limitations of life. What body was I born in? When was I born? Who was I born to? And an artist, unlike most human beings, has the wherewithal to find form to actually mine the mountain of their life, and pull out of it things. Then they have an audience. The audience becomes a collaborator. Some of them are quite raw, but when they’re juxtaposed to each other they become something different, and that’s the art process.

What role does memory play in your work?

Memory is very, very important right now. I’m 73 years old. I think I’m probably in the last 10 years of my creative life. I’m making work, but I don’t feel that I know what it has all added up to. Each time I do a work like the Story/Time: I Feel the Earth Move Under My Feet, I’m finding out a little bit about what my life is and what art is.

These are also stories of resilience, a theme I see throughout your career. Where does that inner sense of resilience come from?

I will do with you what I do with my dancers and say, “OK, well where are you from? Who gave you life? Who gave you the sense of yourself? Who were those people? What was the narrative that you were taught? Why do you believe in yourself? Why do you believe? Did you ever wonder what gives you validity to have an idea?” I’m answering a question by asking a question. That is why I quote people like Maya Angelou and James Baldwin, people who have dealt a great deal in understanding the struggle to exist, the right to exist.

I grandly say I am a child of slaves. My mother and father were potato pickers, but I’m descended from slaves. Survival, it was taken for granted that you will, you must survive. Now, as an alienated late-20th-century person it’s maybe not enough just to survive, but what is the meaning of what you’re doing? I’m a big, big fan of Hannah Arendt and as she reminds us, and she learned from Heidegger, philosophy is not about truth. Philosophy is about finding meaning. So, if you want to say anything about me as an artist, yes, I am quite philosophical. But assertive of some social meaning. I choose movement, I choose human bodies, I choose language and memory and poetry. That’s the stuff that I have given myself to fight the darkness with.

The Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company performs at Guild Hall on August 15; guildhall.org