By Ray Rogers

Ray Rogers: What intrigued you about Cousteau that compelled you to make this documentary?

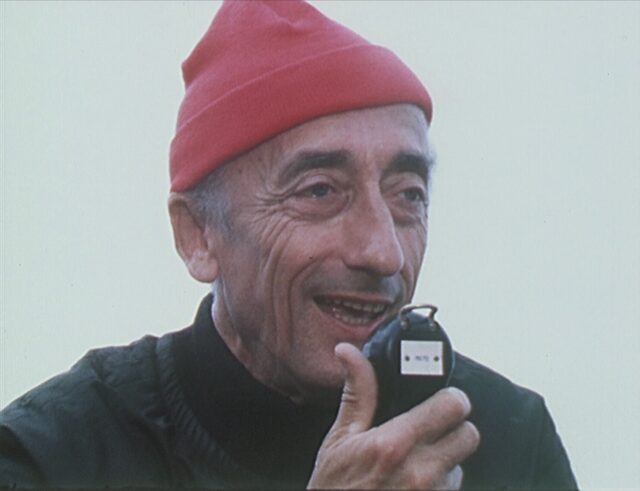

LG: So much! I grew up watching his television show, glued to the TV, dreaming of being aboard that boat. Cousteau was a big part of my childhood. About six or seven years ago, I was reading a book about the undersea world and how it first reached a global audience through his show. I realized his legacy as the pioneer of undersea imagery wasn’t known to the current generation. That was the kernel. But then when I began to dive in, so to speak, what I realized was that there was a great story: the evolution of a man who was at first drawn by his hubris and a conqueror’s spirit, who then changed and had a redemption story in which he became a protector and a siren for the peril of climate change.

RR: I also grew up watching the shows and being amazed by them. I didn’t know that the early part of his journeys was funded by oil companies.

LG: Exactly. I think none of us knew. I didn’t know that he was a filmmaker prior to being this TV personality. I didn’t know that he had pioneered the underwater breathing apparatus that became scuba. There was so much I didn’t know. I thought of him as a great captain on a boat who was showing off beautiful fish. And obviously the story has so many more dimensions than that.

RR: There’s a quote from him in the film where he says that it’s no longer about beautiful little fish, it’s about dealing with the fate of mankind and…

LG: …nothing less.

RR: Now, decades later, the situation is very scary.

LG: He also said, “We’re throwing blank checks on future generations.” And here we are, sitting there, the recipients of those blank checks, with a huge catastrophe unfolding before our eyes. And with very little time left to reverse some of the worst effects.

RR: The film ends with a note of optimism from him. What do you hope people take away from your film?

LG: Look, in 1992 with the Rio conference [United Nations Conference on Environment and Development] I think there was optimism. There was this global gathering and attention given to the issue of climate change. And almost 30 years later, very little has been done that would have reversed some of the most negative effects of climate change. So while it’s hopeful, it’s also a tragedy that’s still unfolding.

The takeaway is we can all use our paper straws, but at the end of the day the challenge is great and it’s going to require nation states to come together and take bold and potentially initially unpopular action. The message is that we need to look at the hard truths. As individuals we can all do our part in reducing our own carbon footprint, but it’s a much larger global problem that we need to put pressure on our leaders to combat.

RR: You must’ve had tons of footage to go through. How did you go about piecing this together and telling the story of not just his mission, but of the man himself?

LG: We had an embarrassment of riches in terms of footage. Cousteau was a filmmaker, first and foremost. At least at first, in his early life. We spent many years working—myself alongside National Geographic—to gain access to the archives. And when we did, there was a gentleman in France, an archival expert, who had been working with the Cousteau Society to organize it. We came up with a wish list of everything we wanted to see and then it became a period of listening to Cousteau and trying to sculpt. I found this with Nina Simone as well [in making What Happened, Miss Simone?]; when you listen to these individuals being interviewed, they often come back to the tendrils of their life that changed to inform that. As a filmmaker, my job is to listen to them speaking beyond the grave and shape a story that is truthful to their journeys.

Becoming Cousteau screens at the festival on October 10.