By Julia Szabo

By Julia Szabo

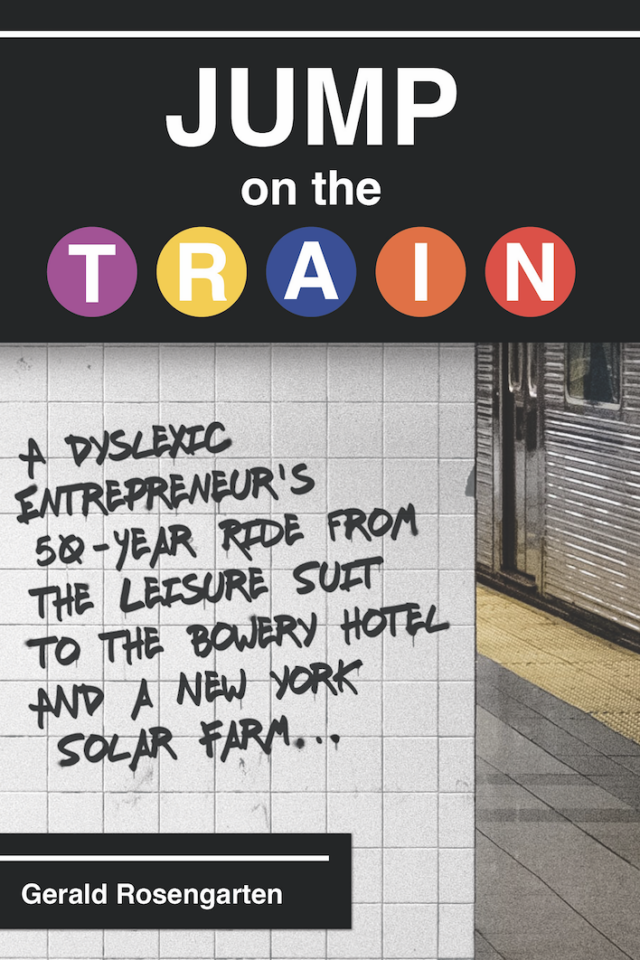

Jump on the Train is more than the title of Gerald “Jerry” Rosengarten’s new book—it’s also the Brooklyn-born serial entrepreneur’s lifelong guiding principle, fueled by his hometown’s storied subway system. “When you live in New York City, you invariably hear an old saying: ‘You either get on the train or let it go by.’ This urban adage not only applied to my daily commute, but it has been the metaphor of my career… I often have found myself jumping from one subway line to another, heading in many different directions.”

Rosengarten’s book is a riveting, reader-friendly road map of one dynamic journey, with as many inspiring lessons as there are potential rapid-transit routes to take. Like a train running at top speed on an elevated outdoor track, the nearly 300-page, 12-chapter read has a thrilling pace, with panoramic views, from the perspective of its open-minded, compassionate author, who graciously offers his lifetime of business savvy as a multipart teaching lesson. (Rosengarten considered his fellow dyslexics, as well as vision-impaired readers, by recording an audio version of the book.)

His narrative ranges like a fast-and-furious romp across the New York map, from midtown’s Garment District to ’70s-era Soho’s artists’ loft spaces, with additional stops in the East Village, Alphabet City and even further afield: on Long Island, then in Florida, London and Moscow. Proving that to “jump on the train” is very much a state of mind, Rosengarten’s agile brain still aerobically train-jumps, even though his primary mode of transport these days is no longer an actual train but rather a sleek, white Tesla.

His surname means “rose garden” in German, and yet, for his first five decades, Rosengarten’s reality was hardly a bed of blooms; rather, it was a daily battle with dyslexia. Now, with increasing cultural awareness of disability empowerment, it’s evident that the reading challenge affecting some 40 million Americans can be a kind of superpower. “You can’t even imagine what it’s like to not be able to read,” he says. “My book is designed to open up the fact that you don’t have to just succumb to a problem. You can get over the problem. There are so many different ways to do things!”

“Succumb” was never a term in this author’s vocabulary, even when words on a page confounded him. “Most of my life I had to deal differently with the printed word,” he says. ”I had to learn from people as opposed to books. But I never had any problem with numbers. Math I was very good at.”

Acting was another source of strength, and Rosengarten studied at the legendary The Actors Studio, alma mater of Paul Newman and Al Pacino. He learned his parts via memorization, with a little help from friends and family, his brother in particular, who practiced lines with him. These days, virtuoso acting remains a source of tremendous pleasure to Rosengarten, who recalls being blown away by the late, great Peter O’Toole on the London stage.

A short list of Rosengarten’s achievements—from inventing leisure suits and legal loft living in the 1970s, to being the force behind two Manhattan landmarks, The Bowery Hotel and the Theater for the New City—culminates in the solar farm he pioneered in Mastic, on Long Island, as well as the sustainable Southampton green home he meticulously built and still lives in.

Today, dedicated medical buildings increasingly populate what Rosengarten calls “the NYC universe of real estate development.” The first to boldly jump on that train back in 1984, with the Greenwich Medical Arts Building, designed for doctors’ offices, he calls the building “a ‘drizzler,’ because it would keep splitting out cash flow.”

Hearing about ingenious colorful screens enabling fellow dyslexics to read, Rosengarten pushed to devise a targeted method to help children, calling it the Rainbow Reader. His proudest achievement, he says, was successfully installing the first of 700 lifts at the Florida community where his parents retired, and where the powers that be had mistakenly decreed that the machines simply wouldn’t work. “The lifts added 10 years to those seniors’ lives,” he says.

It’s a fine example, he adds, of how “I enjoy inventing change.” Thanks to dyslexia, “I would see what wasn’t there more than what was there, and I’d make it happen. It’s like I’m always proving something, always going further.”

That, of course, is what game-changing entrepreneurs do, and Rosengarten—who cuts a dashing figure on the East End, in Giorgio Armani black linen—is pleased to take his well-deserved place among other business leaders he admires. One of his peers, the late Steve Jobs (although the two never met), even inspired Rosengarten to invent a watchband for the Apple Watch.

“People get hot and sweaty doing sports with the Apple Watch, and it can get uncomfortable. This slides on your wrist and you don’t feel like you’re wearing anything.” The inventor, his wife and a few friends are happily wearing the first prototypes, whose oval shape symbolizes Rosengarten’s next train ride: Run For the Sun, “which will utilize the solar farm as a running track for society’s most vulnerable: high school students of all learning abilities. All can compete—they don’t have to be track stars—with scholarships and Apple products awarded to the winners. My goal,” he concludes, “is to uplift high schoolers, because they’re our future.” His vision is for all solar farms in the country to join in this environmental event. jumponthetrainbook.com