By Regina Weinreich

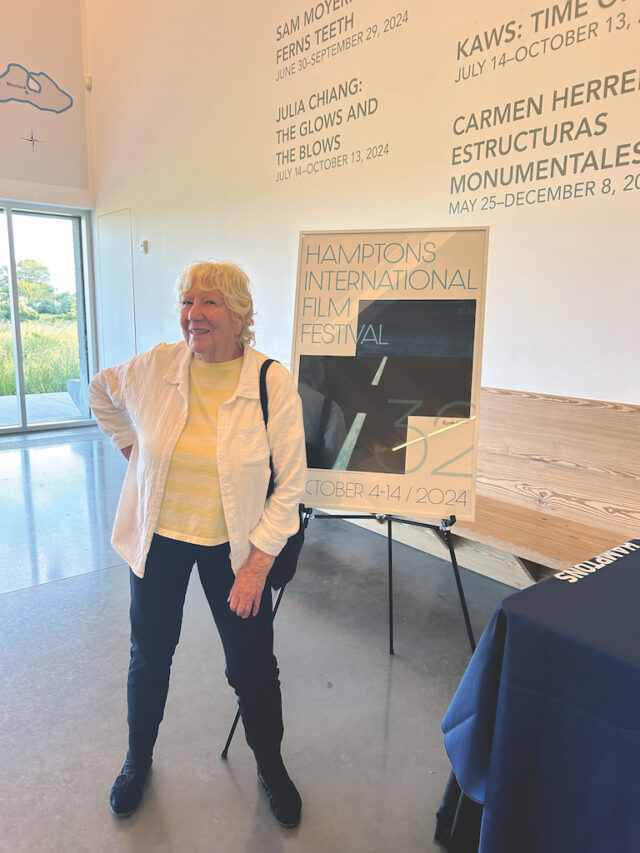

A plane of midnight blue with a single broken line against black suggests a road in the poster for the 32nd annual Hamptons International Film Festival: This variation of Mary Heilmann’s signature painting, “Maricopa Highway” (2014), after cities in Arizona and California, offers a definitive path for cinematic art in this unique beachy location, now the artist’s home and main studio.

In a new documentary, Mary Heilmann: Road, Waves & Hallucinations, the artist, a Bridgehampton resident, says, “My paintings are informed by this biographical story—what I saw driving around America, on roads, looking at surfing, looking at waves.” Hallucinations, visions from the alternative San Francisco culture she got involved in as a teen, inform “my nonobjective abstract painting.

“I like to sit on the beach and look at the waves—at sunset—I watch the sun go down behind me and the moon come up over the ocean, and then I look at the ocean waves, the sky, the sea, the sand to get inspiration for color.”

Mary Heilmann’s life story begins on the West Coast: her youthful desire to be cloistered like a nun giving way to a “mission to be someone and have an identity in the world. That was unusual,” she says of the difficulty for women to break through in art. Her father was a surfer, and an engineer who built freeways. She marveled at the math of that. “I love looking at how the freeways were built—geometric.”

When she was 13, he died of cancer. She recalls wearing black stockings and meeting the Beat poets as a high schooler in San Francisco, living near Haight Street. Rebellious, painting “to make the sculptors mad,” she came to Manhattan to be part of the art world. She tells vivid tales of downtown life and the dealers. Occupying a studio across from The Odeon on West Broadway, she says, Philip Glass stopped by to fix her pipes—“he was my plumber.” She moved to Chinatown; Steve Reich came and played. Holly Solomon climbed the stairs wearing a mink coat and bought work with wads of cash. In the mid ’70’s, she moved to Tribeca. By the early ’80s, she left Holly Solomon. Looking for a dealer, Heilmann called her friend Ross Bleckner, who introduced her to Pat Hearn. Holly Solomon was conservative and commercial. Pat Hearn was more radical.

After all the road trips, often driving alone, she chose to live out East: “I came out here 30 years ago. My main studio is here, because this is where I am all the time. I came during COVID. I liked working out here. I love being part of the wonderful scene. Being chosen to create the HIFF poster is part of that. I was a loner as a kid. Now I am in the middle of everything: cool museums and wonderful farming all around.”

Today, at 84, she has two dealers that complement each other: Lisa Spellman of 303 Gallery, a local favorite, and Hauser & Wirth, with its global clout. Assessing her career, she says, “All over the world many people know about Mary Heilmann. That’s a wonderful thing.” Looking at her art, she feels a sense of pride: “When you get something right, it’s amazing.”303gallery.com, hauserwirth.com