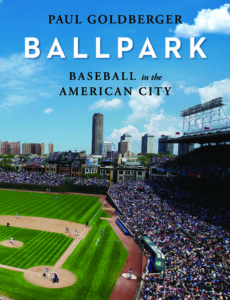

James Merrell: Paul, first, congratulations on your just-published book, Ballpark: Baseball in the American City. I imagine as a boy your love of baseball, and perhaps of ballparks, came long before your love of architecture did.

Paul Goldberger: All kids seem to like baseball. I have a very clear memory of my father taking me to Yankee Stadium for the first time, and the incredible brilliance and beauty of that bright green field, right there in the middle of The Bronx. The power of that rural ideal, embedded in the middle of the city, has stayed with me. I have never walked into a ballpark since and not felt that sense of wonder.

JM: You have written about architecture for a long time, and about houses since at least the early 1980s, with your seminal book The Houses of the Hamptons. I’ve been looking forward to asking you about today’s architectural fashions, which are decidedly modern, and what you think they can tell us about our times.

PG: Modernism in this country has always had two related aspects: Early modernism was a truly avant-garde movement, aesthetically and sociologically, with roots in European utopian socialism. But then there’s that aspect of the modern that is merely aesthetic—clean, fresh, comfortable, and even economical. At first, modernism in the Hamptons was economical too, using inexpensive or off-the-shelf materials.

JM: That period, the late 1960s, was very experimental. I remember seeing a photo of Richard Meier’s Saltzman House in my parents’ Newsweek. It wasn’t like any other house I’d seen. Architectural fashions then morphed into the postmodernism of the 1980s and ’90s. Do you feel they were also experimental?

PG: Oh, yes. The first new shingle-style houses seemed refreshing. The modern houses that preceded them had begun to look too sculptural and isolated, not like members of the community. So, when Robert Stern and others started building their first neo-shingle style houses, that seemed wonderfully promising. But it turned out to be something of a dead end. They inspired some good houses, and rather like the first wave of modernism in the Hamptons, the postmodernism of the 1980s and ’90s produced a lot of terrible stuff. The pendulum began to swing back.

JM: People often say fashions cycle. But that discounts the impact of ideas. In the 1920s, for instance, modernism was a culture-wide revolution. And the architects of the 1960s and the 1980s had their theories. Do you see theories at work in architecture today?

PG: Remember that architecture, like culture, always follows the money. It likes to take the lead, but in many ways it follows. In this period of enormous prosperity at the top, people have sought a modern design that is more sumptuous than anything.

Recently, following the tsunami of shingle-style houses that had washed over the Hamptons, architects seem to have fought to make modern houses comparable in grandeur to, say, the great Georgian houses of the 1920s by architects like David Adler, Delano & Aldrich, and others.

When Charles Gwathmey built his de Menil House in East Hampton, in the early ’80s, it was a foreshadowing of this trend toward grandeur. And it showed that the aesthetic could be adapted.

JM: I have to remind my clients that every house is handmade—even those production houses in suburban developments—and that the only limitation now is our imaginations.

PG: Putting aside the fact that it is very difficult for most people to afford creating a house with an architect, making a house is an enormous personal statement that requires one to spend huge amounts of time in the mirror asking ‘What am I looking at?,’ ‘Who is this person?,’ ‘What do I want?,’ and ‘How do I wish to show myself to the world?’ That’s why people will often liken the process of designing a house to psychotherapy, and the job of an architect to that of a therapist.

JM: Very true!

PG: In fact, not many people feel comfortable doing that. Some do, of course, and then there are people with great creativity who don’t have a lot of money, but put interesting and unusual things together to create an identity. It’s very similar to how people used to assemble wardrobes, especially in the 19th century. We live in an age that is virtual as much as it is real. The house represents real physical space and a material culture that pushes away from the virtual. And yet, it is also a retreat and a private space, at a time of increasing isolation.

JM: I’ve come to think the “dream house” might represent the last opportunity that most non-artists will have for a significant immersion in a truly creative experience.

PG: And what better way to resist the many forces pushing us toward homogenization, to what some call the mono culture? It’s an interesting challenge going forward.

Purchase Goldberger’s book, Ballpark: Baseball in the American City here.