by Ray Rogers

Ray Rogers: Hi Alexis, how are you doing?

Alexis Rockman: Great, I’m sitting out by my pond in Warren, Connecticut. We moved here over the last year, gradually. I moved my studio up here also. It was COVID-related, but I also decided I had to leave my studio of many years in Tribeca just because it was getting a little depressing being in a basement, even though the price was right.

RR: Tell me about the new body of work being shown at Guild Hall, Shipwrecks. The series is so beautiful, even when imparting this impending feeling of doom. They’re gorgeous.

AR: Thank you. I’ve always liked that sort of innate conflict between terror and lyrical beauty and the sublime. What is more beautiful than a shipwreck in the ocean, right? No matter the conditions. It’s hard to go wrong. I had started thinking about doing a project about shipwrecks in early 2018 when I made a number of works over the years of ships that were distressed or wrecked, so to speak. And I had witnessed one with my wife when we were traveling to Antarctica in 2007, and she ended up being the correspondent for The New York Times, the on-the-spot reporter, because she’d written for the Times for years. And through my interest in the natural history of colonialism and invasive species and exploration, I know that ships are involved in so many of those areas. It made sense to have a big net to throw out there. That’s how I try to organize my life, to give myself opportunities to do something I love to do, and I’m proud to stand by.

RR: And to learn, too.

AR: There’s a strange educational component for someone who was a terrible student in high school, and embarrassed by my SATs, then vowed to never have that feeling again once I got to art school.

RR: What kind of historical research did you do for the series?

AR: Each painting has very specific references that I had to go through, to give it a sense of credibility—from the 1944-45 U.S. ships for the USS Indianapolis, to the exact genera of plants and animals that were brought by the first inhabitants of Hawaii via outrigger canoe, to the type of paddle wheel steamships that were involved with the SS Sultana [1865 disaster]. I can assure you, there are mistakes. Those were pointed out to me by one historian who was a maritime specialist. Well, you can never get it all right, but it helps with the credibility of the project.

RR: Themes around climate change and humans’ destruction of the planet have been present in your work throughout your career.

AR: Since the ’80s, and in a more intuitive level in terms of the biodiversity crisis, I was making paintings about extinction in the ’80s. But when I heard about climate change by a scientist I was working with—I started to reach out to collaborate with scientists around 1994—I thought that was a terrible nightmare. I wasn’t convinced we would solve it for a number of reasons. I was certainly more right than I dared imagine. I was very concerned then, but now I’m just terrified.

RR: “The Things They Carried,” features a bat and a pangolin in it. In what ways did COVID influence that work?

AR: I just relocated up to Sharon, Connecticut, where we rented last summer while we were renovating where we are in Warren. And I was corresponding with Dan Finamore, who is the associate director of the Peabody Essex Museum where the show is now, who is a big resource in terms of content. Dan was joking around and said, “I guess it’s time to paint pangolins.” Because they are possibly involved in being one of the vectors of COVID, as you may know. So “The Things They Carried” has a langur monkey who brings jungle fever to India, the Norway rat who brought us the bubonic plague among other things, bats that have been involved with COVID as well, the palm civet is involved with SARS, and so on. To be clear, these animals are unwitting, and not guilty of anything other than being unlucky enough to be intentionally or unintentionally involved with their habitat being destroyed, and being used as food by humans. The finger is not pointing at them; the enemy is us.

RR: How does it feel to be kicking off Guild Hall’s 90th anniversary summer season?

AR: It was on my bucket list to show there ever since I started going out there in 1989, when I shared a house with a bunch of friends in Amagansett. I had a little studio in the shed.

RR: Guild Hall this summer is also screening Ang Lee’s brilliant Life of Pi, a film for which you helped provide visual inspiration.

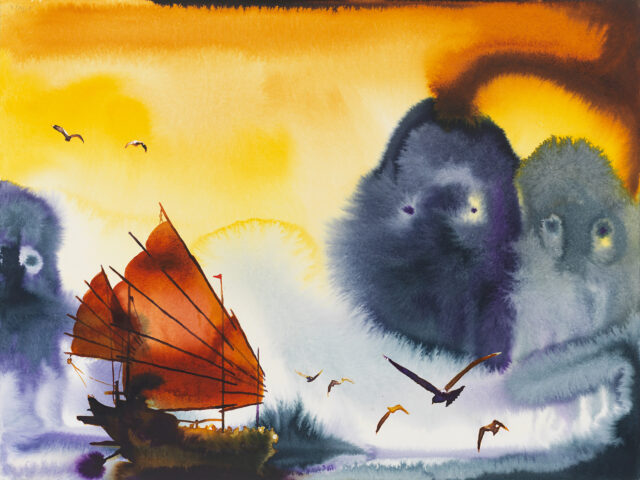

AR: I got a phone call from a mutual friend of my wife and myself, [producer] Jean-Christophe Castelli, who has a house in Montauk, asking me to meet with Ang about possibly contributing to the look of the movie. I grew up thinking I’d be involved somehow in visualizing films like King Kong or Citizen Kane or Blade Runner or any movie that had such a strong influence on me as a kid. Even in my early 20s. When I realized I could actually have a life being an artist and a painter, I was slightly crestfallen, though thrilled to have any life in the arts at all. Because I didn’t see how I’d ever be able to do both. I went to Ang’s loft in Soho. I was thrilled because I think he’s an incredible director. He had just done Brokeback Mountain, which had absolutely nothing to do with the Life of Pi, but Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon has incredible visual styling. He asked if I was available and I was shaking and sweating and saying, “I think so.” Over the course of three years I worked chunks of the calendar. The first thing I did was to come up with six very elaborate watercolors to show to the studio what Ang wanted his movie to look like. To make a long story short, there was a year and a half where I was not involved whatsoever. Then I came back and designed the island and a couple of images from the shipwrecks—speaking of shipwrecks. Then I designed this sequence called Tiger Vision, where they go to the bottom of the ocean and somehow become this one entity. That was an idea that Jean and I had on a platform on a subway on the 1 train going downtown. And I can’t tell you, it was an incredible thrill to see these things developed—and they looked exactly like I had imagined, but often better.

RR: That scene that you’re describing is so memorable.

AR: That was not in the script, and I was just thrilled to have it. I could drop dead tomorrow—that was one of my goals. Back in 2008, I used to tell my friend Phil Tippett, who was a great stop-motion animator who worked on Star Wars and Jurassic Park, that my lifelong dream was to design a monster. And he said, well you may get it. That’s a big thrill.

RR: Will you be at Guild Hall for the opening?

AR: Absolutely. I haven’t been to the Hamptons since the fall, before COVID hit, but I’m looking forward to reconnecting with people I love. I’ve made so much work out there over the years in Sag Harbor when I was renting there, and I did a project at Parrish about the local ecology, so I feel really connected to it.

Shipwrecks is curated by Guild Hall Executive Director Andrea Grover and is on view from June 12 to July 26 at Guild Hall, 158 Main St., East Hampton; guildhall.org