Barnes Coy Architects is celebrating its 30th year designing modern houses on the East End. In 1993, when I was 2 months old, my parents moved from Greenwich Village to East Hampton. My father, Christopher Coy, founded Barnes Coy Architects that year with his childhood friend and fellow architect, Robert Barnes. I grew up on tours of Barnes Coy construction sites, with my father patiently explaining to me the wonders of concrete and glass. I especially loved peering into the meticulous wooden (now digital) models of their houses. Barnes Coy Architects, having designed over 250 houses, has played a role in shaping the face of modern architecture in the Hamptons. As a writer, I’m happy I get to be the one to talk to my father about BCA’s 30th anniversary.

Camille Coy: I want to begin with the future, rather than ending on it. How would you describe Barnes Coy Architects’ direction for its 30th year?

Christopher Coy: Barnes Coy Architects continues to focus on the design of the house as the most important building type in our lives. I feel so privileged to have been able to design in a beautiful place such as the Hamptons, and I look forward to continuing my practice and meeting new design challenges.

Modernism can refer to specific styles of design, but it can also describe a conceptual approach. How do you understand modern architecture, and how has that understanding shaped Barnes Coy?

The modern movement liberated architecture from the practice of mimicking historical forms. Houses had small windows and pitched roofs because of limitations in building technology, which gave rise to what we now refer to as “traditional” architecture. A sense of warmth can be conveyed by materials, no matter the form. A modernist study can be paneled in warm wood and a large open living space, transparent on both sides, can be bracketed on the ends by hand-laid Irish stone walls. More people are realizing that familiar materials such as wood and stone can provide emotional warmth and comfort in the context of well-designed open floor plans.

The built environment is the major component of our daily experience, so architecture past and present, should first be beautiful. Clients have often spoken of a sense of spiritual calm they feel in our houses, which I attribute to the experience of nature being near to them. We use long-span steel structures to allow for expansive walls of glass to bring the experience of nature inside the house.

You have designed houses in deserts, swamps and jungles, but as an architect you are often confronted with the intensity of oceanfront. From what I’ve seen of how you work, which is a lot as your only child, I know that you focus on the design of the house as a way toward a heightened experience of the ocean, a way to capture the best views and the calmest mornings.

The question of what to do with the ocean beach, that magical place where the land abruptly ends and the ocean begins, is always present in our studio because Long Island, especially the roughly 36 miles east of the Shinnecock Canal we call the South Fork, is essentially a sandbar in the ocean. We are surrounded by water. The quality given to the light by breaking waves throwing salt spray into the air has brought artists to the East End since the 1880s. Except for the occasional set of large French doors leading out onto a terrace, most traditional beach houses had small, double-hung windows with muntins dividing the glass panes and fracturing the view. An oceanfront house should surrender to the enormity of the ocean it confronts, with as much transparency as possible. A paradox is created: You want to feel one with the beach and the water, and yet you also need to feel protected from the power of the ocean. A successful modern design has poetic visual dialogue between the ocean and the house.

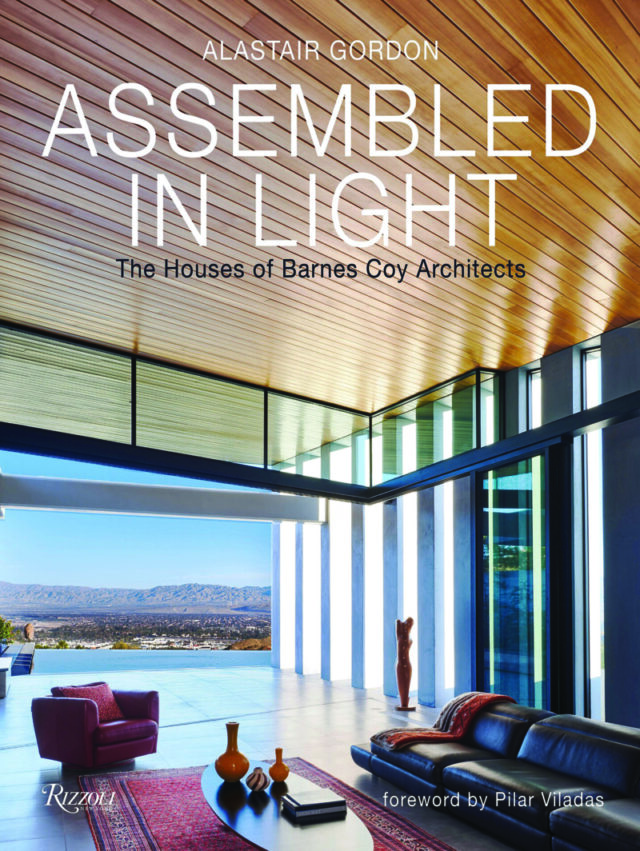

Robert Barnes was my godfather and your best friend since you were 10 years old. You met on the beach here in the Hamptons, where you would one day design houses together. Your book, Assembled in Light: The Houses of Barnes Coy Architects, written with Alastair Gordon, was published by Rizzoli in 2020. What was it like to look back on such a large body of work?

It is unusual for a friendship to last a lifetime, and even more unusual for it to turn into a creative partnership like the one I had with Rob [Barnes passed away in 2018]. Organizing my thoughts about our work for the book, in the time between running the studio and my travel schedule, forced me to look back. Preparing the book allowed me to look at our body of work with a detached, critical eye. I took the time to consider how I thought about residential architecture and Barnes Coy, and I was able to discern a line of logical progression in our work. The book process encouraged me to look to the future.

Barnes Coy houses are site-specific and intensely custom, meaning that you work intimately with your clients to ensure that every aspect of their house is designed in consideration with their lifestyle. How do you tailor your designs to meet the specific needs of your clients while still creating beautiful architecture?

Most clients’ programs follow similar requirements: Everyone needs a kitchen, bedrooms, bathrooms, gathering spaces, etc. It gets interesting when there are very specific requests, which can be challenging. Usually these have to do with designing spaces for entertaining, indoor sports or specialized areas for anything from meditation to wellness to gallery space. We once installed a vertical cold plunge pool below a basement floor. People are increasingly interested in having custom health and wellness spaces. Another request was for a bridge that doesn’t go anywhere but ends abruptly, dangling midair toward the Pacific Ocean, pointed at the sunset for the perfect views. Because every family is an institution unto itself, learning about them and putting that knowledge into our design is what keeps us stimulated.

On Sundays, our family outings were always a visit to your construction sites. As a kid, I loved walking through the steel framing, trying to imagine the different rooms. Tell me about your process, from sketches through to a completed project.

I still go on those Sunday outings! I like to walk through the site and be alone with the project during its early stages, when it’s developing from a two-dimensional sketch into a building on the landscape. The actual process of getting from a sketch to a manifestation of that idea in a built project, is mysterious. Sketches develop into drawings, and details expand on the intention in the drawings. Then I discuss the drawings with a builder, and the important collaboration between architect, builder and client begins.

Barnes Coy Architects is based in the Hamptons, one of the most beautiful and desirable places. You’ve loved it here your whole life, and I feel this the most when we’re out sailing together, looking back at the shoreline. The Hamptons has played a huge role in your approach to architecture and your sense of design.

What first comes to mind about this collection of villages and hamlets we call the Hamptons is its relationship to water. The 5-mile-wide South Fork is pierced by harbors, inlets, wetlands, marshes and estuaries. The area became an incubator of early modern architecture. The most famous example is the work of Pierre Chareau, who designed the Maison de Verre in Paris. Chareau came here after the war, and designed Robert Motherwell’s studio and house in East Hampton in 1947. The light and views, not only of water but of the extensive farm fields, continue to inspire architects. I can remember farm fields going all the way to the dunes, and as a kid I thought that the gentle fields were like a solid version of the ocean.

Thank you, Papa, it’s good to talk through Barnes Coy Architects’ 30th year with you. It’s kind of amazing to see so many of your sketches and ideas expressed as built forms—as you say, you are devoted to truth and beauty.

In my work, I travel to many parts of the world, and when I come back to the Hamptons I am once again confirmed in my belief that it is one of the most beautiful places on Earth. What better place to create architecture? barnescoy.com