by Chris Cuomo

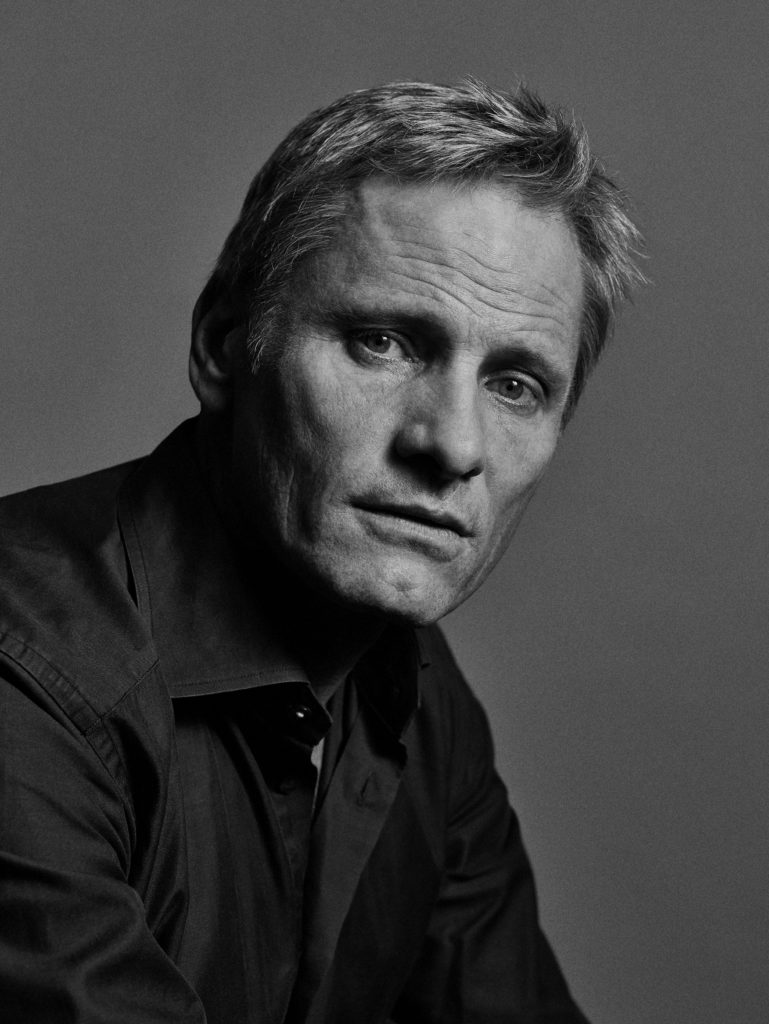

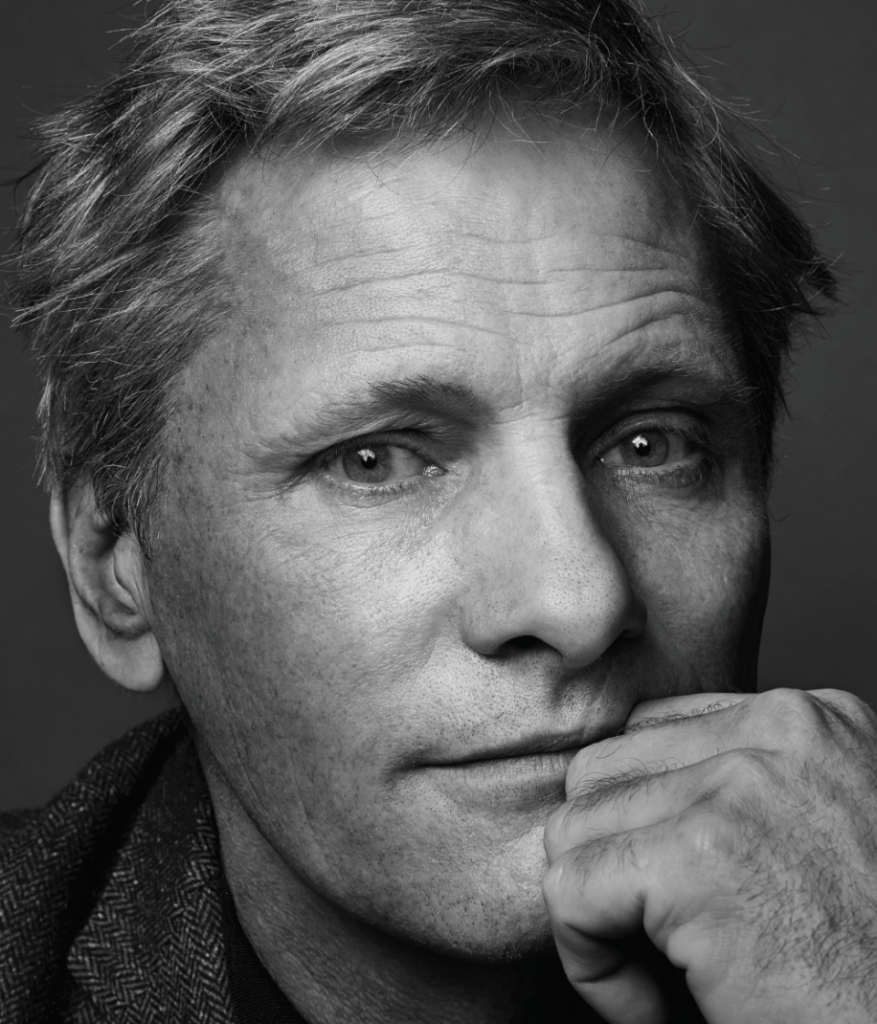

Viggo Mortensen is known for challenging, rugged roles like the legendary Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings series, in addition to parts in Captain Fantastic and The Indian Runner, but the versatile actor, who is also a published poet and musician with several CDs to his credit, never inhabited anyone less like himself than the racist, burly bouncer he plays in Green Book.

The title of the Peter Farrelly-directed drama refers to The Negro Motorist Green-Book, which outlined hotels in the segregated South from the 1930s to the 1960s. Mortensen’s character, Tony Lip, is juxtaposed with Ali’s Dr. Don Shirley, a famous African-American classical pianist virtuoso, whose depth of education and sophistication sharply contrast with that of Mortensen’s character. It doesn’t hurt that the screenplay by Brian Hayes Currie, Nick Vallelonga and Farrelly is perhaps the best of the year—funny, moving, profound, and a great history lesson. The unlikely story of two characters—brought to life with beautiful music and comedic highlights from Farrelly—is a story of love, friendship and courage, as the duo become lifelong friends and save each other along their road trip through the deep South.

Dr. Shirley’s tour through restricted Southern venues in 1962 takes place six years after Nat King Cole (who by 1956 was a household name) ventured back to his hometown in Alabama to perform, only to be attacked on stage by members of the Klan. Green Book is also an important exploration of how social attitudes toward race and sexuality have evolved, a reminder of how overt segregation was just a generation ago. As Mortensen told me, Green Book “shows that the cure for ignorance is experience.” While we see Mortensen’s character growing increasingly sophisticated due to the influence of Dr. Shirley, he is already accepting of his traveling companion. There is none so poignant a “beautiful reveal” as the one where Shirley is exposed as a homosexual and Lip comes to save him. Simply, as a bouncer, Lip had been around gay people and was not bothered—but Shirley, in his vulnerability, offers him more money fearing he might leave his duty. But Lip rejects the pay raise, and as Ali observed to me, his character is made “extraordinarily aware of the value of this relationship and how deep his love is for him.”

My profoundly Italian-American husband, Chris Cuomo, says he has never seen anyone who is not from that world portray this type of role so on point. So I asked the two to sit down and have a conversation about it in Mortensen’s birth home, New York City, before he ventured back home to his private life in Spain, where the Oscar buzz on Green Book will continue to quietly build around him. —Cristina Cuomo

CHRIS CUOMO: How did you take a caricature like Tony Lip and give him so much texture and depth?

VIGGO MORTENSEN: Always, when accepting a role, I begin with the same question: “What happened before Page One of the script?” Over the 36 years that I have been working as a professional actor, I believe I’ve learned how to more efficiently answer that question in order to build characters from the ground up, but the question remains one that has an infinite number of answers, big and small, no matter whether the character is based on a person who existed or is entirely fictional. With the challenge of preparing and playing the role of Tony “Lip” Vallelonga for director Peter Farrelly, I had the good fortune of being able to access a lot of firsthand information from the Vallelonga family and friends of the real-life Tony, as well as audio recordings of him speaking about many things related to the Southern road trip with Don Shirley that are the heart of Green Book. Additionally, I was able to observe his body language and listen to his vocal inflections and accent in the movie and television parts that he played. The idea with this character, and with every character, is to avoid creating a superficial caricature by learning to understand as much as possible the point of view of the person I am embodying, never to judge that person. This, hopefully, will allow my fellow actors as well as the eventual audience to learn about the person I’m playing, and not superficially judge or dismiss him.

CC: If you weren’t familiar with that period in American history or The Negro Motorist Green-Book, how did it impact you when you learned about the story?

VM: I was familiar with the history of the USA in the pre-Civil Rights Act era, but I learned to pay attention to certain subtleties that the script for Green Book provides us regarding varying forms and degrees of discrimination. I also learned many things from my primary acting partner in this production, Mahershala Ali—in particular, how he viewed certain aspects of the story and his character, Doc Shirley, as an African-American. An example of what Mahershala added to Green Book can be observed in a scene that takes place in a Memphis hotel lobby. At the end of that scene, Tony says to Shirley that he ought to essentially stop worrying about playing the classical music he was trained to perform, because the hybrid of jazz and classical music that he has come up with is unique. People love what he does, and only he can play that way, Tony tells him. As scripted, Shirley then ends the scene by saying “Thank you, Tony.” Mahershala wisely suggested adding a final line: “But not everyone can play Chopin—not like I can.” This speaks to the fact that Shirley, like Nina Simone, had been prevented by his record company and discriminatory concert venue restrictions from performing and recording as a classical music pianist solely because of the color of his skin. There is absolutely no reason that Shirley should accept at face value Tony’s well-intended but uninformed opinion as to what music he ought to aspire to play. That was a great addition to that particular scene, and to our movie story.

CC: It’s such an eclectic group—you, Mahershala, Peter Farrelly—how did it work together?

VM: We were a great team. Pete set the tone early on with us and with everyone else in the cast and in his crew by saying “I don’t know everything. If anyone has a suggestion about anything we can do as a team to improve on what we are filming, however small or insignificant a detail it might be, I want to hear about it.” Green Book was made in an ideal spirit of joyful collaboration, and, as a result, the movie is unashamedly compassionate and sincere.

CC: How do you think the film fits into our political and cultural moment?

VM: This is a movie that provides valuable civics and history lessons, and that serves as a cautionary tale for any society at any time. While I would agree with anyone who points out that U.S. society at this time is especially polarized, I feel that the problems of discrimination, class schisms and racism are challenges for every generation in every country. Children, when they are very young, tend to play freely with their peers without giving much importance to differences in skin color, language, ethnicity, nationality or physical handicaps. As they get older, they somehow learn from their family and social environments to differentiate, to place importance on these factors. These learned attitudes lead them to see themselves as above, beneath, or beside the point with regard to their peers.

Hopefully, through re-education, individuals can re-learn to “play nice” again, to eliminate aspects of their ignorance through direct experience, through imagining themselves in the skin, place and environments of others. The face and vocabulary of discrimination evolves. It is stubborn, tribal, based in ignorance and fear, and must be combatted by us all with factual information and direct, open exposure to those who seem, on the surface, to be different from ourselves.

CC: Our nation is more divided than ever. What do you want people to take away from Green Book?

VM: The simplest answer to that question would be to say: If Don Shirley and Tony Vallelonga can learn to get along and respect each other, anyone can. To those who perhaps expect or crave a more militant message, a less happy resolve to the movie—true as it is to the historical facts of the relationship between these two men as depicted in Green Book—I can only say that I am glad that our movie does not merely preach to the converted or demand that we pay attention; it invites us to pay attention, to be compassionate, to listen and reflect.

CC: How did you weave Tony Lip out of a poet’s soul?

VM: If you are referring to me as a poet and Tony Lip as something other than a poet, I would say that Tony proves, in our story, to be a compassionate poet. His line, when he is suggesting that Shirley consider contacting his family, that “The world’s full of lonely people afraid to make the first move” is a perfect example of that. That is a beautiful statement, and one of many pieces of fine writing in our movie’s screenplay. Probably Tony’s noblest quality is to eventually demonstrate to Shirley and to us that he is capable of learning, evolving and improving as a human being.

CC: What was the hardest part for you, emotionally, in doing Green Book?

VM: Being a hard-core Mets fan, having to pretend to be a hard-core Yankees fan.

CC: You have looked very good for a very long time. How do you do it?

VM: I don’t know of any particular tips other than eating healthy food, sleeping well, and getting regular physical exercise. My guess is that I am blessed with good genes from my mother and father that have allowed me to compensate for burning the candle at both ends during certain periods of my life. I recommend drinking unsweetened yerba mate tea, if you can adapt to its bitter taste. It is good for digestion, and provides energy without the jitteriness that drinking a lot of coffee or strong tea usually brings.

CC: What has been your favorite phase of your life?

VM: Right now. What was is no longer, and what comes next has not happened yet.

CC: What do you want to do in the next 10 years?

VM: Travel as much as I can, both mentally and physically, and learn how to understand the world, other people, and myself better.