Artist Anne de Carbuccia travels the globe capturing the beauty and the sorrow of a world that’s being decimated by climate change and human behavior. Begun six years ago, her immersive body of work—a mixture of sculpture, shrines, photography and documentary film—feels more prescient than ever.

By Ray Rogers

RAY ROGERS: The images you’ve created for the One Planet One Future series evoke thoughts of time, life and death—our own lives and that of our planet. What was the impetus for this body of work?

ANNE DE CARBUCCIA: As an artist it’s always hard to understand where your creativity comes from, but I started this project over six years ago in September, and it’s my way of channeling my own anxieties, both as a human being and as a mother, for the future. I have three children, aged 11, 21 and 22. Six years ago nobody was really talking about climate breakdown, but I had been traveling a lot. I come from an island—I’m from Corsica—and I’ve been seeing the world change really fast. This is a life project, so probably what you see in the art is like a résumé of everything that I’ve worked on and loved. I’ve got an anthropological background, so I’m trying to do something that I’ve studied and has always fascinated me. You can probably argue that it’s the first artistic expression of human beings, in a way, if you go back to ancient times; people have always been creatively inspired by what they’re afraid of and what they admire.

RR: Tell me about the use of the skull and hourglass in what you call your “time shrines.”

ADC: The skull and the hourglass are classic symbols of 15th, 16th and 17th century vanities, or still life painting. Being French, I have this very classical background, so still life painting always fascinated me, for many reasons. They were done in areas of transitions or of great plagues, or great transitional moments for human beings. The vanity is something that as a symbol always fascinated me and also I think in a way its significance got lost with time; in contemporary art, the skull is a skull. The real significance of the vanities and why they are used was lost. It’s not a symbol of death. It’s a symbol of choice, it’s here to remind us we’re all mortal, but that we have a choice in life, everyday we can choose between a positive and constructive life, or a superficial and vain life. We’re going through the biggest transition in the history of humankind; it’s very important, because it’s about each and every one of us right now. It’s all about individual choice. We’re past pointing fingers, we’re past saying who’s right or who’s wrong; it’s just about taking a stand. We all need to take a stand.

RR: Absolutely. It doesn’t even matter who’s right or who’s wrong. It matters what we do now.

ADC: So that significance of ‘you have a choice’ every day in your life. And I’m reminding you of this in this work, you can choose. So that whole, in a nutshell, my art is about bringing together what has always fascinated me and also things that are quite extreme. Because it’s like shrines and paganism and honoring things in nature or animals. But it’s also about this deeply religious significance of 16th and 17th century still life painting, which is about humbleness, and reminders, and about accepting our mortality and making the best of it, as opposed to refusing it and just ignoring it and leading these very superficial lives.

They say that there’s two types of photography: creative photography, which is the expression of an idea; and documentative photography, which is documenting a period or a moment in time. I like to believe that my work has both.

RR: It does.

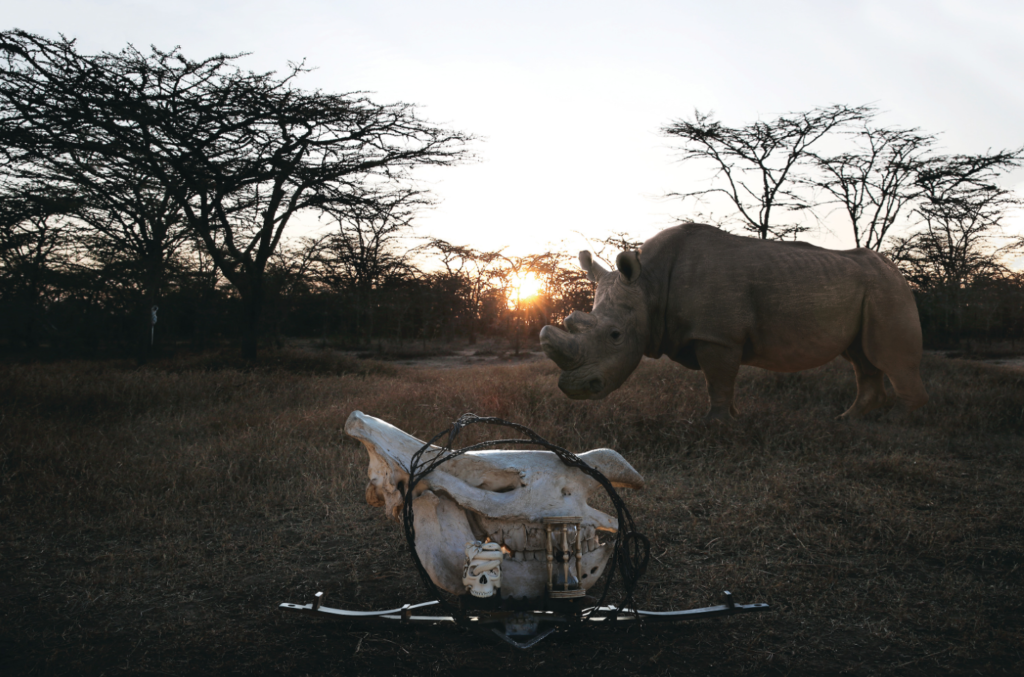

ADC: It’s both creative and expressing with the time shrine, creating an installation, but I’m also documenting our planet. Over the past six years, a lot of the places I’ve documented have already [been impacted greatly]. I’m addressing all our biggest challenges, from climate breakdown to endangered species and extinction, to forests and jungles to trash. So six years ago when I started, very few people got what I did. It’s like…what do you mean? She’s going around the world with an hourglass and a skull and she’s creating time shrines; nobody really kind of embraced it except for a few collectors, which is what really made me feel stronger. Today, everybody understands my work, I don’t need to explain it.

RR: What shifted?

ADC: The global consciousness. Climate breakdown is not really something that was addressed five or six years ago. Now, whether you believe in it or not, it’s everywhere and it’s being addressed and we’re living in it, actually. We’re already starting to adapt. So now I’m shifting, I’m into adaptations. Until now I’ve been showing art saying, “It’s still here, but this is the problem,” and I’m showing what’s left, I’m showing the beauty that’s left. A lot of the work I’ve done now is gone, the images don’t exist anymore. For example, endangered species I’ve photographed, like Sudan, who was the last Northern white rhino on the planet. He’s dead.

RR: That’s a tragedy. You’ve seen extinctions and erosions and all kinds of damage. What keeps you hopeful?

ADC: It’s what keeps me active. I’m not hopeful. I’m active. You can’t be hopeful when you know what I know. But you can be active. Do something. And I think if everybody is active, we can avoid the worst. We will all have to adapt, how much we need to adapt. And also because I have kids. So I’m doing this for them. I’m doing it for the next generation. I’m doing it as a citizen, I’m doing it as a citizen of our planet. I choose Earth. I’m not dreaming about living on Mars. I love our planet, and this is where we belong, it’s perfect for us. We need to protect it. We need to really help it, and help ourselves.

RR: It’s wild because these images are so beautiful and ethereal, but also heartbreaking. For instance, the piece that features the medusas (or jellyfish) tangled in plastic.

ADC: Yes. I think today you can communicate better with beauty in art than harsh words and difficult images. I think people kind of just shut off, or shut down once, if you provoke them with violence.

RR: It could be too much.

ADC: Yes, it’s too much. So there is definitely a seductive part in my art, even though I’m addressing difficult things. Not everybody likes looking at the vanity, people are fascinated by it but others are disturbed by it. But aesthetically it functions. If you will look at it, whether you like the art or not, you will question, you will be interested in why, and then you’ll go to the caption. The caption has a poetic comment, but because I collaborate with so many scientists, it also has scientific data behind it. So that’s my scope: It’s the beauty and the sadness. I can say that beauty can save the world. That’s where I’m putting my vote.

RR: Has the project impacted your diet choices?

ADC: Definitely our eating choices are going to be key in the future—food and water, obviously. But food for two reasons: for health reasons and for your impact on the planet. Reducing your meat consumption, especially cow meat, is key. So I don’t eat any cow meat, for example. The only reason I still have meat in my diet is because, for instance, if I go for three weeks in the Himalayas, all the Buddhists have to eat meat too, because that’s all there is: yak. But I really resist it. If you’re eating meat every day, and you do meatless Monday, that will already have a huge impact.

RR: Any top tips on what readers can do in their daily lives to make an impact?

ADC: Eat local. Eat seasonal. Reduce your meat consumption by 50 percent. Completely get rid of disposable plastic—refuse it. Those are all things that are very easy to do. Please, please get a bamboo toothbrush. I’ve been underwater and seen turtles with toothbrushes up their nose. That’s another thing: As a consumer, you can make a really big difference. Don’t let anybody tell you we have to wait for governments to make a difference, because we’re the ripple and we can really make a difference.

RR: Your work’s been exhibited all over the world, from Manhattan to Milan to Moscow. Do you notice differences in how people react to it, or is everybody on board with it?ADC: Yeah, the latter, that’s what’s so shocking. For example, when I did my show in Moscow or even Naples, I thought, they’re not gonna get it. They have so many other issues and priorities, why would they get this? And they all got it. I think it’s because my art is emotional—I’m trying to find the keys to your heart. But I was very surprised in Russia, because I was being exhibited in a public museum, so the people—they don’t have anything there, they don’t even have proper TV, and the people can only afford a public museum because it’s very cheap—so I got a lot of very lower-middle-class people, and I had babushkas hugging me. We’re one species, and we’re all in the same boat, and people know that. Around the planet, very much, everybody knows.