By Steve Garbarino

Still defying gravity like her impossibly free-floating architectural masterpieces, Dame Zaha Hadid passed away at age 65 five years ago this spring. Yet her world-spanning portfolio of buildings—embodying the balance of form and function—will live on, remaining timeless and relevant well beyond the 21st century.

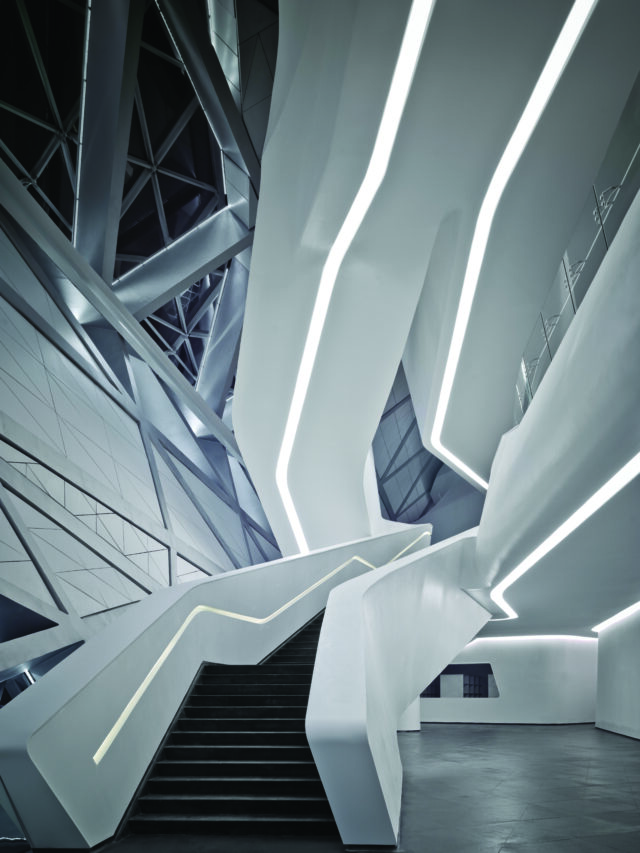

Often designed for public and civic usage—from opera houses (Guangzhou) to Olympic aquatic centers (London)—her works are visual spectacles singular to the first woman to ever have won the coveted Pritzker Architecture Prize (2004). Concrete, steel and glass were her media. Her personality was all about class, sass and a fashion savvy recognized by such collaborators as Chanel and Fendi. Born in Baghdad, the Iraqi British designer was nicknamed the “Queen of the Curve,” which suited both her cantilevered structures and voluptuous countenance.

Perhaps her interest in civic structures was born out of growing up with a father who was the head of the Iraqi Progressive Democratic Party. The first major commission built was the Vitra Fire Station in Germany. And in the years up to her death in 2016, she was still making statements of high drama and graceful sustainability.

That includes Gloucestershire’s Forest Green Rovers Eco Park Stadium, a forthcoming ark-like soccer stadium made principally of timber, spanning 100 acres. Not to mention a futuristic, 11-story condominium on West Chelsea’s High Line, floating like a spaceship near the Hudson River. “Basically, it’s sculpture,” said the developer of the building, Gregory Gushee, executive vice president of Related Companies in 2015 of the curvilinear tower, which includes retail space and an art gallery.

In a profession dominated to this day by men, Dame Hadid largely brushed off male critics who called her a diva and difficult. “As a woman in architecture you’re always an outsider,” she told The Financial Times. “It’s OK. I like being on the edge.” That included her affinity for wearing Comme des Garçons, Issey Miyake and Prada. Ever the populist, however, she also collaborated on footwear designs with Adidas, Lacoste and Melissa, bringing molded plastic into her oeuvre.

Dame Hadid’s influence as an environmentally conscious space-rejuvenator has clearly crossed over to a new generation of architects, including the firm of Lacaton & Vassal—helmed by Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, the designers who this March won the Pritzker Prize for their makeovers of 1960s-era high-rise housing projects in France. Adding airy terraces and balconies—let’s say it was a little more complicated than that—they’ve turned drab into fab in nearly all their reinventions of impoverished areas that now glow with hope and light.