By Michael Mailer

Who is the heavyweight champion of the world? Who is the greatest? Who floats like a butterfly and stings like a bee? Can you embrace him? Can you even name him? I can’t, and I grew up a fan and a practitioner of the sport.

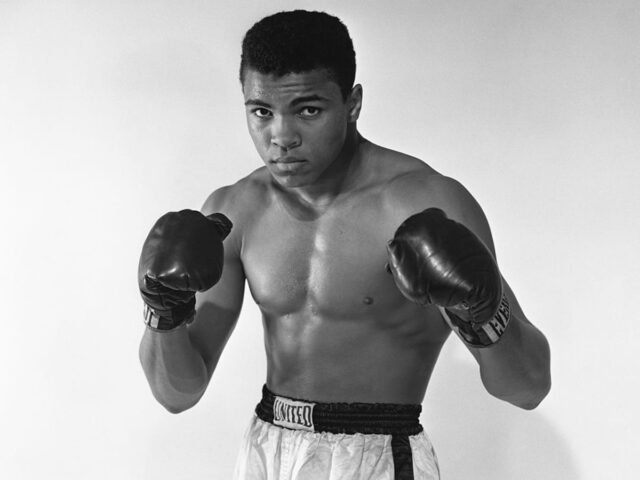

Growing up in Brooklyn, we used to compare ourselves to the greats: Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, Jack Dempsey. The list went on. Never did a main event, a heavyweight title fight, escape our attention that we wouldn’t hang out on the stoops till late afternoon arguing who was going to take whom, in what round, and with what kind of punch or combination thereof. Occasionally a lighter-weight division champ would enter the dialogue, but it was the heavyweights by whom you’d measure yourself. If your man was the man, then you were, too; if he got knocked out or dethroned, you were toast. That is, till the next main event gave you a chance to realign your identity. Indeed, the heavyweight champs were gods, and in the case of Muhammad Ali, perhaps God himself. He was not only the self-declared greatest, he was the greatest! A deity is perhaps second only to J.C. in name popularity—maybe even greater, as the Chinese knew Ali before they knew Jesus.

But that was before the invention of what’s commonly referred to as “alphabet soup”: a smorgasbord of sanctioning bodies (organizations empowered to declare champions) that sprang from the void like the mythic Gilgamesh. After all, if you could imagine a “champ,” even on paper, then a “title” was on the line and more money was to be made.

It worked for a while. Initially when the boxing world splintered into three groups—WBA, WBC and IBF—it was a challenge to see who could unify the title. Mike Tyson succeeded and had the greater glory for it, but as soon as he accomplished that feat, it seemed like several more boxing organizations sprung up in his wake to offer their own title holders. Before long the sport—at least in the heavyweight division—diluted itself into near nonexistence. And the heavyweight gods disappeared.

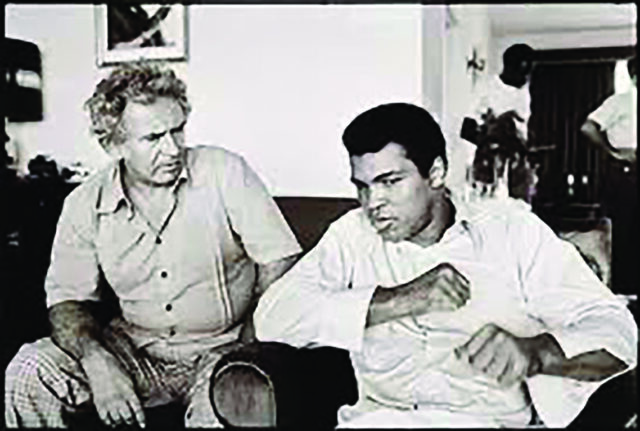

But that’s now. Back in the day, it was a very different story. I remember as a boy my father took me to Ali’s training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. Ali was training for the first Leon Spinks fight, and it was a chance to meet my hero face-to-face. As we passed through the gates of his estate, we drove up a long driveway lined with white rocks emblazoned with the names of former heavyweight champions. It was like traveling up the road to Mount Olympus, and the anticipation in meeting Zeus himself was palpable enough to spread with a knife.

We pulled into the compound and were escorted into the gym facility and placed in seats beside the ring. The room was filled with press, trainees and fans. A large, brooding sparring partner climbed into the ring and started stretching. Ali showed up without much fanfare—but he didn’t need any introduction. Everyone leaned forward and whispered as the champ weaved gingerly between the ropes and entered the ring. He was fully adorned in headgear. He threw a full obligatory warmup punch and showed off a sluggish version of his famous footwork. Then the bell rang. The sparring partner pursued Ali with the languor of a gorged lion, throwing a few lazy jabs, which Ali blocked easily enough. It was almost as if they were following some choreographed ballroom dance. So long as the sparring partner respected his rhythms, the great Ali would float slowly and carefully.

Then the unthinkable happened. Someone forgot his dance move, and Ali caught a short left hook to the chin and went down. With stunned gasps the crowd watched Ali slowly get up. The sparring partner went to his aid with near dread on his face. Ali brushed him off and called an end to the sparring session. I turned to my dad with disbelieving eyes. Had this actually happened? Did my god just suffer the indignity of a knockdown? My father said it was a stunt to drum up hype for the fight but I didn’t quite believe it. There was a melancholic look in Ali’s eyes that spelled a quiet defeat.

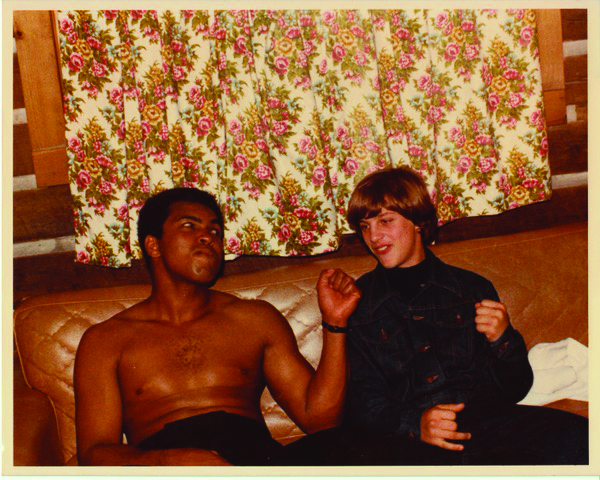

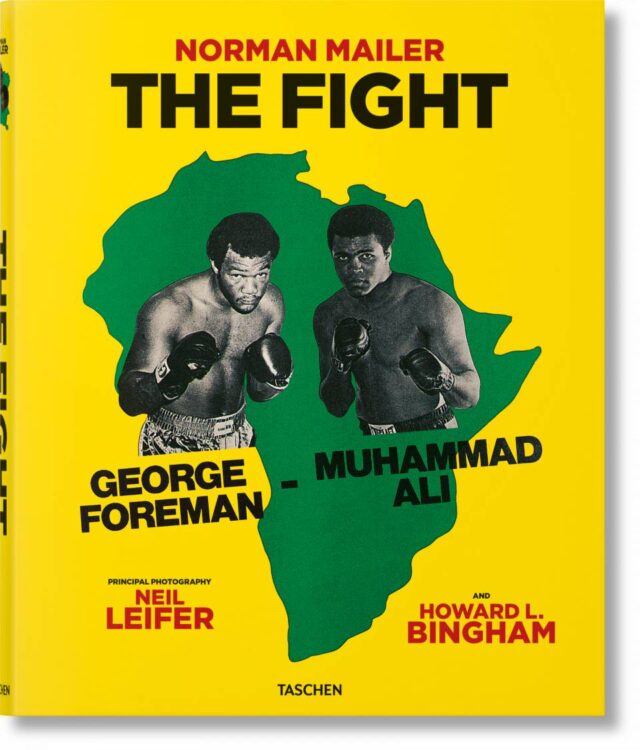

When Ali disappeared into the dressing room, we were plucked from our seats and ushered into his inner sanctum with a few trusted confidants. My dad and Ali exchanged warm but quiet hellos. They had shared some meaningful moments over the years, the Ali-Foreman fight being one of them, but mirth was not the tenor of the moment. As Ali disrobed he suddenly took notice of my presence—I was the only kid in the room and he must have been amused by the wide-eyed stare of this youngster beholding his wonderful nakedness. “He’s my son,” my dad proudly proclaimed, pushing me forward to meet the Great One. Before I knew it, I was propelled onto the couch next to Ali, and his dark mood evaporated. He couldn’t help himself. He genuinely liked kids and started hamboning me. I was petrified but went along with it. At least by now he’d put on a pair of pants. It was hard enough sitting next to a god, but a naked one? It was too mind-bending for my preadolescent brain.

A month later, Ali lost to Leon Spinks. It was a split decision, but he’d clearly lost. Spinks was the new heavyweight champion of the world and no one quite believed it—least of all Spinks himself. I remember weeping in disbelief. And it seemed that everyone in attendance as the camera panned the arena was weeping as well. It was the end of an era, the end of boxing on a rarefied level—boxing as we all knew it.

Ali, of course, came back and won the rematch. But he was a mere shadow of his former self, forced to box well beyond his prime in order to support his sultanlike retinue.

For a number of years the sweet science continued in Ali’s absence, and a few great heavyweights followed (Mike Tyson notably among them), but greed ultimately consumed the sport; everyone and their mother became an instant champ, and the heavyweight division began to wither like a stillborn tree sterilized of fruit.

My father used to say to me, “If I could punch the way I write, I would be the heavyweight champion of the world.” Given the world of boxing today, I believe he would rethink the equation.