Paula Weinstein: Susan, why now? What motivated you to make this film now?

SUSAN LACY: I read Jane’s book, My Life So Far, when it came out 13 years ago while doing a series I created, called American Masters, and was always looking for good stories, particularly about women. I strongly believe that you shouldn’t make a film about a great artist if you don’t have the material to tell the story with. There is something in Jane’s story that everyone can relate to, whether it’s difficulty with a parent or child, insecurity, body-image issues or unfaithful husbands. Her candor about these things and unrelenting honesty, including looking at her foibles and mistakes, is such an inspiring journey to self. That’s what this film is about.

PW: And Jane? As I look at the film, I certainly admire it a lot. I think it’s wonderful. We’re in a very big moment of transition in terms of the next generation of feminists. This is a perfect switch here. What do you hope young women will take from the film, and was that part of why you decided to tell it after writing your book?

JANE FONDA: I wish I had seen a documentary like this when I was younger, because I believe it would have made me think about the importance of not just drifting through life like a waif in a stream, but really putting your oars in the water and trying to determine what direction you want to go in. This film shows that you don’t have to get stuck where you are. You don’t have to settle for what people tell you you’re supposed to be, or how men define you. You can keep moving. But it has to be intentional. I think that’s one of the biggest messages for young girls. Also, that they’ll go after you if you’re an activist, but you can survive. I mean, I’m here.

PW: Susan, the film is interestingly structured in five acts. What made you make this choice?

SL: The notion of acts is actually embedded in Jane’s book, as she said when she left Ted [Turner] and decided to write her memoirs, she wanted to understand her first two acts. She says it in the film, too, about her third. So acts were in my head and when I started making the film, I realized that often in making portraits of artists, who have really made a major cultural impact, the third act is hard. It’s usually sad and the decline. And I thought, “The act Jane’s in right now is every bit as interesting as the first.”

PW: It’s way better.

SL: It’s way better, exactly. You’re [Jane] the opposite of what many of us call the third act problem.

PW: Jane, did you have any feelings about it?

JF: I thought it was really smart. It’s not how I divided my book, but Susan discovered that it’s a gender journey, so that’s how she divided it up. I appreciate it.

PW: I found it very bold. But I want to remark, as a feminist and friend, that one of the things Susan did in the film, is really make it clear that Jane led these transitions.

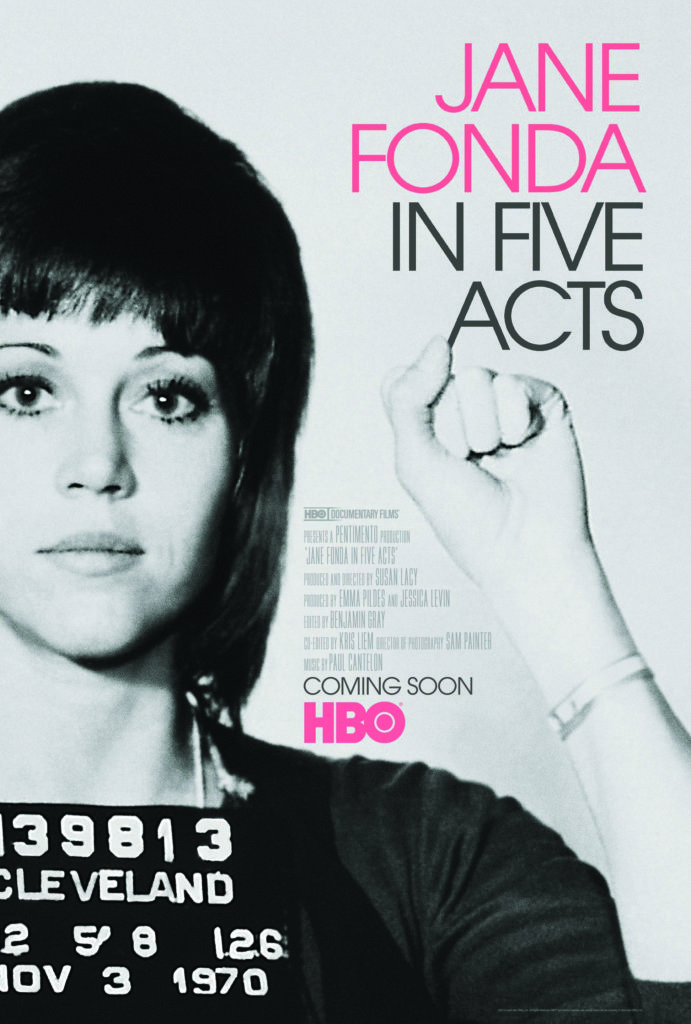

SL: At the root of this story, there is a through line of integrity and bravery. You might have been, as you’ve said in your book, defined by men, but nobody told you to go to Vietnam except you.

JF: Yeah, they did.

SL: You were encouraged to go, I know, by people to use your celebrity to help bring attention to what was going on, but you made those decisions. You chose your path. And I don’t think you give yourself enough credit through most of the telling of your story.

JF: Well, when I was about to turn 60, I was married to Ted Turner, and realized, “Oh, my God. This is gonna be the last act.” Now, I think I’ll live longer than 90 because if Gloria’s [Steinem] gonna do it, I’m gonna do it. I used to ask, “Gloria, why do you want to live to 100?” And she said, “Because I want to see how it all turns out.”

SL: What was going on with you at the moment that made you write the book, and be willing to spend all that time digging so deeply?

JF: I didn’t want to be like Columbus, who didn’t know where he was going when he left or where he’d been when he got back. I wanted to figure out where I’d been, so I’d know where I was going. I researched myself. It’s something I highly recommend and it requires things like carefully looking at photographs, talking to other people and trying to figure out who your parents were. Why did they act like they had duct tape over their eyes? Why couldn’t they reflect you back to yourself with love? Who were their parents and why did they behave the way they did? That’s what I started to do.

I didn’t know there was a word for it, “life review,” that psychologists encourage people to do. It transforms you because you realize it had nothing to do with you. It wasn’t your fault. If they couldn’t love you, it was their problem. You can forgive them because you understand bad behavior is the language of the wounded. You have to break the cycle and move in a different direction.

Right now, older women are the fastest-growing demographic in the world and we’re living a whole adult lifetime longer than our parents and grandparents did. It’s good to be a late starter. I’m a late bloomer, and I’m really glad. Everybody’s born whole, but does anybody get through childhood in one piece? I don’t think so. But it’s good that way, because then when you get older, you actually feel when you begin to move into yourself again. It doesn’t just happen. You have to be intentional. You have to work at it, study, meditate—you have to do a lot, but it can happen.

SL: There’s a wonderful scene where Jane talks about doing Barbarella, which she didn’t want to do at first, but Roger Vadim convinced her she should do it, and he directed her in it.

JF: He wanted me to do a striptease for the opening credits and he promised me that the letters in the credits would cover everything. He lied. I was so nervous that I got drunk, really drunk, on vodka. Then when we went to watch the film the next day, a bat had flown between the camera and me, so we had to do it over again. What you see in the film now is the same thing with a hangover. [Laughs]

SL: But it was in France that you became politicized, meeting with a lot of soldiers. Also, Simone Signoret, who was very involved in the student protests, and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Bouvier.

JF: Simone Signoret was a great, great, movie actress in France. She befriended me when I went to France and took me under her wing. She used to take me to anti-war rallies where Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir would speak. She never proselytized; she would just expose me. After I became aware of what was going on in Vietnam because I had spent time with soldiers who were resisters, I went to Paris and was confused about what to do. I went to Simone’s home in the country and I just remember ringing the bell and her opening the door and saying, “I’ve been waiting.”

SL: I think for as much as you learned from the men you were married to, they learned a lot from you. Each of them has said at the end, “This was the love of my life. I fucked up.” In the first section, as a child in the Santa Monica Mountains, you talk about looking through the window of a home nearby, and seeing what you thought was a family. Do you think much of your life has been a quest for that?

JF: I’ve never thought about it. I guess so. I think it’s because of my son. He always loved having a big family, so I’ve tried to create a big family for him.

SL: I do think that you’ve been looking for that. I mean that’s my interpretation anyway. It may not be conscious, but that you were building toward a life with a family. And look at the family you have now.

JF: I know—and I’m single! I’m so happy! It’s just me. I live in a place now that’s all mine.