by Ray Rogers

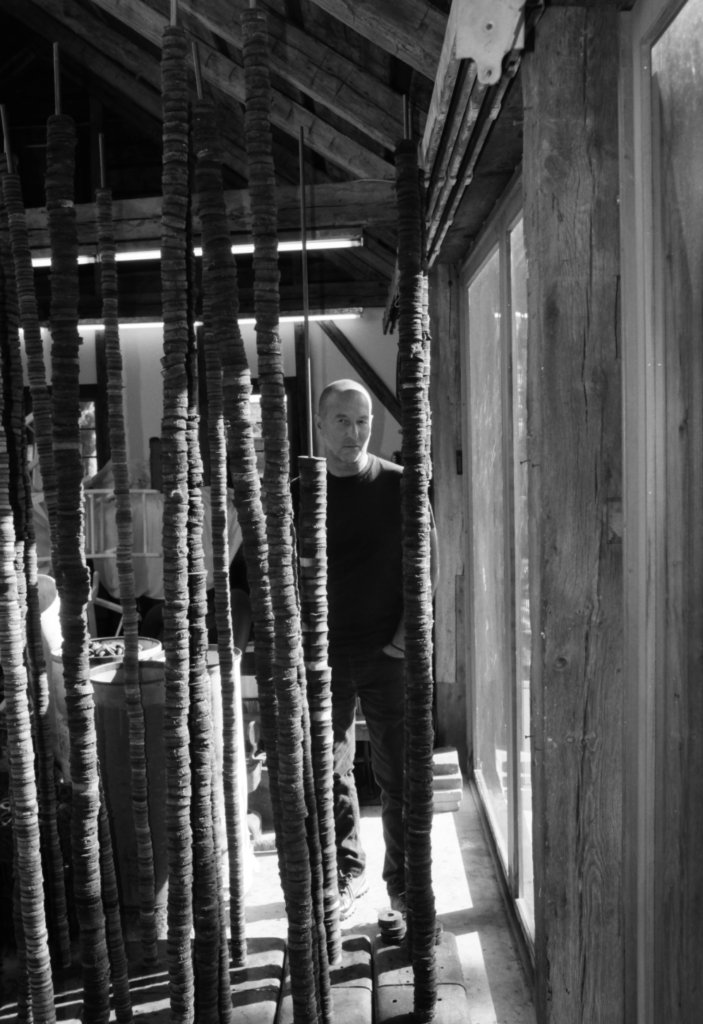

Ray Rogers: Since we are in East Hampton, let’s start by talking about “twenty-two,” your sculpture at LongHouse Reserve, which was installed in 2018. You’ve referred to it as possibly symbolic of a “tribe”—the grouping of 22 standing pillars, resembling human spines, or earthworms sprouting up from the ground. I know there can be a fine line between abstraction and realism or figuration. Does it speak to you differently when you see it today, or think about it now?

Helmut Lang: “twenty-two” was inspired by a grouping of fykes [long bag nets kept open by hoops], which appear all over the East End. They bring to mind a tribe or some kind of gathering or pagan ritual. They do also evoke the spinal column, and reference the scale of the human body, as I do in many of my works. It invites the viewer to consider the body less as a hierarchy of limbs and organs, but as a meshwork of equivalent and interchangeable elements. Examined closely, the kinetic work becomes distinctly biomorphic, changing infinitely depending on the variables of the surroundings.

Being a site-specific sculpture outdoors, its output varies greatly depending on the light of the day, the season of the year and the density of shadows the pillars cast on the ground, which are constantly moving throughout the day. The pillars are in a permanent position, but they appear to have movement throughout the day. I see the installation as I did when I handed it over to the public, but everyone who is seeing it is making a different connection or has a different impression, which is exactly what the installation is supposed to do.

RR: What was the installation process like—what kinds of considerations were made? Anything to say about the site location, what may be different/new in seeing the work outside of a gallery’s four walls?

HL: The artwork was made as a site-specific work, and its conception and installation process involved visiting the LongHouse grounds a few times to find the right placement for it. It then took two days to put it into a formation that I felt was interesting and strong enough to exist on its own, while being able to interact with the public. Visitors are actually intensely engaging with it. This my first outdoor installation, although there are quite a number of my sculptures that—in terms of the material composition and their formality—are able to equally live inside or outside. I am very interested in creating more site-specific works and outdoor sculptures. I think there is a different magic happening when artwork is placed in an outdoor context.

RR: What did it mean to you to have a piece here, in this iconic East Hampton location?

HL: LongHouse is a unique place that attracts visitors across generations. I have my studio on Long Island, and I work year-round out here, so it felt quite organic to have a piece on semipermanent or permanent view at LongHouse and be part of the local community. The uniqueness is that the ground displays sculptures of artists without the confinement of their origin or stature in the art world. It is a vision curated by Jack Lenor Larsen, supported by his great team that nourishes the grounds and spirit every day.

RR: When you first came to East Hampton, was the rich history of artists working out here over the years a draw? That magical light?

HL: I came out here a bit more than 20 years ago, and solidified it as an escape from my extremely busy work life in New York and Paris. I left my former occupation at the end of 2004 to commit myself to being an artist full-time, a practice I had pursued on and off throughout my prior career. I took a half-year break to reset, and during that time, it became somehow logical for me to have a studio here, instead of working from the one I had in Manhattan, as I could work undisturbed and at anytime without restrictions or distractions that an urban place imposes. There are actually quite a substantial number of artists who work out here presently, which is not as well-known as it should be, although the Parrish Art Museum, Guild Hall, LongHouse, The Fireplace Project, the Halsey McKay Gallery and others are making efforts to change that. Of course all of us are somehow aware that we are on art-historical grounds, but beside that it is actually about living in the now and producing contemporary work.

RR: I used to see you running with your beautiful dogs on the beach between Indian Wells and Two Mile Hollow in the late afternoons years back. Is that still a part of your life?

HL: My routine has changed over the years, but it is still part of my life as I live right on the ocean.

RR: There’s something very meditative about silent beach walks. I personally find it conducive to creative thinking and problem solving. Do you find yourself working through pieces in your head like that? Or is it more about creating on the spot in the studio?

HL: You’re right, there is something meditative about it—or exhausting—as I like to walk at a certain speed to clear my head and keep my body in shape at the same time. I prefer to exercise outdoors instead of in a confined space. I use that time to possibly not think about anything at all, and just be in the moment with the Atlantic Ocean. I like water. These moments without special creative purpose or engagement are equally important as the time one is dedicating to conscious activity. Creativity is an ongoing procedure that does not only happen physically in the studio. Many of the unconscious creative impulses are created outside the studio. There is a lot of active and passive time that goes into creating art.

RR: Does your former life as a fashion designer inform your work as an artist?

HL: My former occupation as a fashion designer does not really inform my work. But as I am always totally authentic in what I do, there are certainly similarities in the approach and in the relentless [pursuit] of achieving the best possible outcome. The difference is that I used to create the outer shell for a body, while I am now creating the body itself in the form of sculptures and three-dimensional wall objects.

RR: Were there ways of working or thinking that parallel what you do today—or do you feel it’s a completely separate path?

HL: Well, my brain will always be my brain, and what I am today is the sum of my experiences and life so far. Every choice has its history, and sometimes moments that have been shoved into a corner are waiting for an outlet. I feel that my original intention to work in art was demanding to become a reality in the form of my present existence.

RR: You work with nontraditional material in your sculptures, like, for instance, memory foam or shredded garments from your runway shows of years past. What do you find interesting about materials that have had “past lives”?

HL: I have always worked with nontraditional materials if that was the right choice, without ignoring traditional materials if that was the right choice. Found materials, which I think is what you are referring to, which have had a past life, elements with irreplaceable presence, scars and memories of former purpose, are often the beginning of a process-oriented approach to sculpture. I don’t consciously use the information of where it came from. It kind of doesn’t matter. I’m not literally interested in the history, but rather in the possibilities. I treat it like every other material. As Louise Bourgeois said, “Materials are just materials, and are there to serve you.”

RR: What are you working on right now?

HL: I am preparing for exhibitions in New York, Washington D.C. and Europe. It is all happening from September this year and on, so I will probably not be leaving my studio much this summer.

RR: What compels you to create?

HL: I have always been compelled to create or to curate my environment independently of the matter or subject. That applies to many aspects of my life. This is just what I have to do. I can’t be any other way.

RR: Are creativity and wellness linked for you?

HL: I have to quote Louise again, who said, “Art is a guaranty of sanity.” I feel exactly the same, and being sane is definitely part of wellness.