by Regina Weinreich

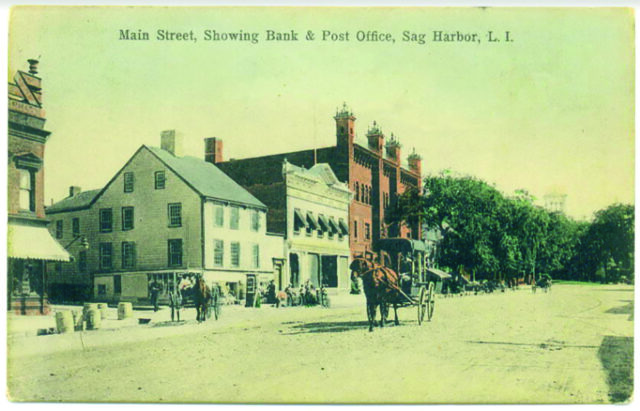

Depicting his salad days in 1985, when Sag Harbor was not yet a “Hampton,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Colson Whitehead in his 2009 novel, Sag Harbor, describes the phenomenon of being “out,” that is, out East for the season “in our summer world”: Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest and Ninevah Subdivisions (SANS), choice waterfront subdivisions of Sag Harbor, purchased by African Americans since the late ’40s. From childhood, his protagonist, Benji, knew this leafy area with summer homes and trappings of middle-class life, paradoxically bougie (“we were Black boys with beach houses”), existed off in the margins, outside the map of Sag Harbor as illustrated in Guide to Sag Harbor: Landmarks, Homes & History, a book in his parents’ living room.

But then, precocious as Huck Finn, and privileged as Benji was, he knew American history does not include everyone. As he roamed free, from yard to unfenced yard, he asked, “Will they allow us to have this?” Benji lands a job at the village ice cream shop, and a first kiss. But as he and his posse engage in the usual adolescent mischief, he’s wise to where the exits are, “in case something racial went down.” After Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, in our Black Lives Matter era, the words send chills.

Since July 2019, SANS has been named to the National Register of Historic Places, following its March 2019 addition to the State Register of Historic Places. Only 2 percent of the 95,000 listings on the national registry for districts are focused on African American historic entries, and SANS is one. In terms of Hamptons mega-development, the distinction may not have much impact on the typical controversies at play: the character of neighborhoods vs. the interests of investors and profiteers. Painter and graphic designer Reynold Ruffins (a founder of Push Pin Studios in 1954 with Milton Glaser) built his summer house in Ninevah in the late 1950s “because there were no alternatives for Blacks,” he says. “It turned out to be the most beautiful place in the world.” Observing buyers coming because “they could get a good deal,” he said recently on the phone, “wealth is a bit smothering for people who feel part of the place.”

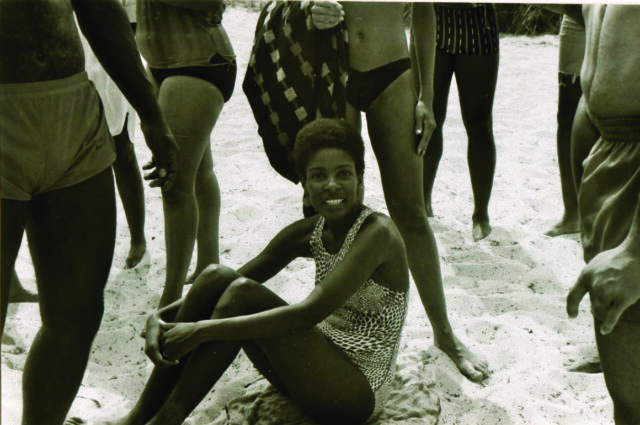

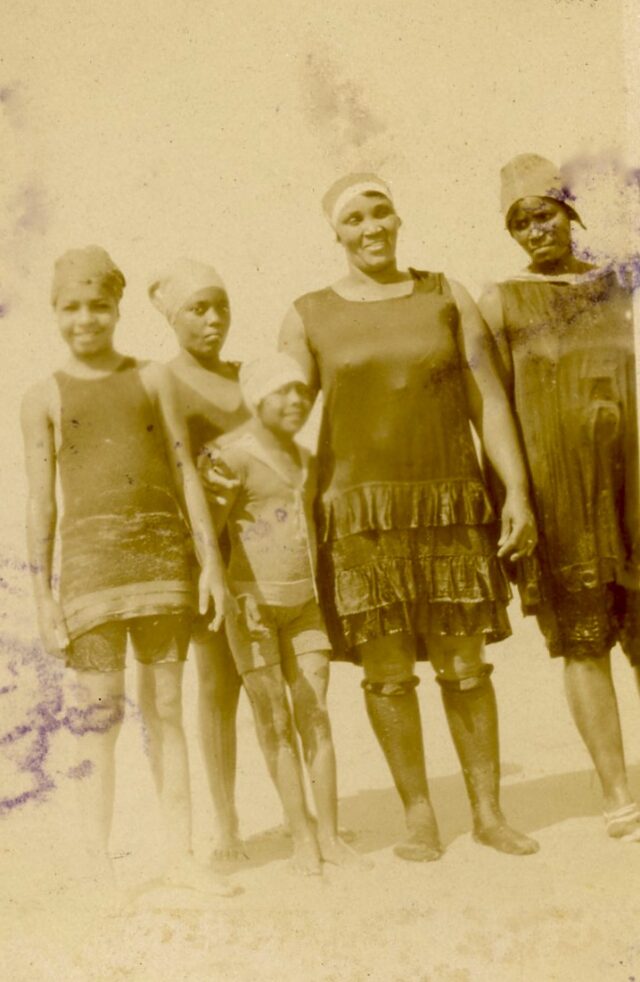

One in a big picture of middle-class Black-owned American beach communities established during the restrictions of the Jim Crow era (places such as Highland Beach, Maryland; Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard; and Atlantic Beach, South Carolina), SANS has a rich backstory. Maude Terry, a Brooklyn school teacher in the 1940s, convinced a landowner to sell a 20-acre undeveloped parcel between Hampton Street and Gardiner’s Bay as a private summer community for Black families, and played a key role in finding buyers and helping them finance mortgages. By 1948, the price of bayfront lots was $1,000; inland, $750. Terry’s sister, Amaza Lee Meredith, a prominent Virginia architect and recognized as the first African American female architect in America, designed at least two residences. By the post-Harlem Renaissance 1950s, Black professionals from NYC built houses, raised families and created a vacation community that attracted the likes of Lena Horne, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes and others—for cocktails, barbecues, soirees, jazz; the community rocked.

Even before: Legend has it, evidenced by a trap door, St. David AME Zion Church had been a stop on the Underground Railroad. Key SANS residents included Edward R. Dudley, a lawyer, judge and ambassador to Liberia under President Truman, the first African American ambassador in the U.S. Dudley had been instrumental in civil rights legislation, along with William Pickens, a founder of the NAACP. Busloads from the area marched on Washington.

Still, when Renée V. H. Simons, a Sag Harbor Hills resident since 2003 and president of the SANS organization, attempted to preserve its legacy by establishing historic district landmarking, she received support from residents, but Sag Harbor authorities declined funding. Fearing the loss of history in the generational changeover of property, “We should be doing more to preserve an African American community in a historic time,” she says. “African Americans carved out their own communities, found a spot that was safe, and through their own private financing, built homes. In those days, African Americans were being redlined out of most areas; banks would not make loans, not even to GIs.”

The effort to designate SANS as a historic district started in 1994, Simons points out. The village considered the possibility, recognizing an expansion that included communities adjacent to Eastville. A document exists stating that areas with cultural significance developed in the Jim Crow era should be revisited. “The village should have come back within five years and extended its historic-district designation,” says Simons, “and for whatever reason it never happened. Part of my motivation was to complete this process.”

A few people, aware of her concerns about retaining the integrity of the community, said, ‘Oh Renée, you just did it because you hated developers grabbing for profits only. How can we save this district?’ A few people in the village said, ‘There’s nothing here.’ I said, ‘There is.’ They said, ‘You’re on your own.’ We fundraised and researched seeking historic support.”

Simons cited several newspapers reporting that corporate America is buying up houses en masse with the express purpose to rent, not for people to have individual homes that they own. “Corporations see this as a new horizon. Instead of stocks, the new paradigm is for home ownership going to corporations. Home ownership was a primary way for middle-income people to amass wealth. That option is being removed for individual families.”

And yet, Simons says: “Millennials are buying homes here, fixing up mom’s house, inviting friends to consider ownership of this property.” Now, in pandemic mode, “People are rethinking what’s important. People who want a sense of community should have those options. The lifestyle here is enviable. We are trying to figure out how to get people to hold on to their homes. In the short term, we have the pride of having the national and state historic district registries.”

When asked whether the registry guarantees that a buyer will not be able to build a 25-bedroom mansion to an inch of its border, Simons replies, “The local registry can prevent a person from maxing out the property. In Sag Harbor, the code already exists governing scale and character; they have to do a better job at enforcement. ‘Local historic district’ for SANS would be another layer of oversight and management.”

SANS is the opposite of Hilton Head Island, an image of development that has lost its soul by losing connection to the cultural history of the Gullah, the once-enslaved people who had created homes there, and by being a transient summer-rental destination, where few actually live. More in the line of the historic campground on Martha’s Vineyard, SANS is still a community. Says Simons: “Whether or not the original owners are there, people treasure it and ask about the history.”

Legacy assured, SANS is on the map.

Regina Weinreich, author of Kerouac’s Spontaneous Poetics and co-producer/director of Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider, lives in Montauk.