By Regina Weinreich

At the newly established Southampton African American Museum, an essential stop on a Hamptons cultural tour, you need more than wall text to explain the old-style barber chair in a ground floor alcove. Best to book a tour with Brenda Simmons, co-founder and executive director; a former assistant to Southampton Mayor Mark Epley, she worked for 16 years to establish SAAM, the first African American museum to be historically designated in the village of Southampton, highlighting exemplary lives of men and women who came north in the midcentury, escaping the legacy of slavery and the Jim Crow South, and this region’s place in that history.

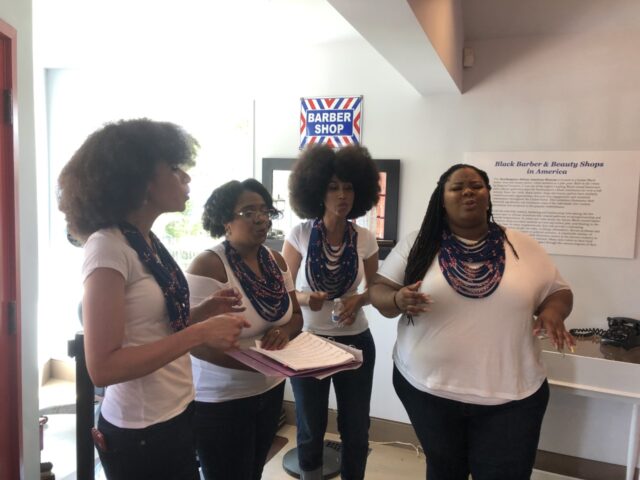

Now a point of pride, identity and Black ownership, the restoration of this modest, shingled, red-trimmed house for public view, the onetime site of a barbershop and beauty parlor that is personal to her, touches on larger community issues, raising the question: When is hair more than just hair? A meeting place for Blacks, the barber/beauty shop was abuzz with information about education, voting and jobs. And now, as a museum, the history of that vibrant community is preserved.

An entranceway mural by Shinnecock artist David Bunn Martine depicts ancestors, illuminating three key themes: “The Great Migration”; the site as barber and beauty shop, and other businesses such as juke-joint restaurants owned and frequented by Blacks; and the story of Pyrrhus Concer, born in Southampton on March 17, 1814, in slavery. Shown riding a whale, he was sold and taken away from his mother at age 5, worked on a farm, and taught himself to be a ship’s steerer. Eventually, he became a whaler out of Sag Harbor, and was aboard the whaling ship Manhattan that was the first American ship to visit Tokyo in 1845. An education fund he set up is still active today.

Other notables include Emanuel Seymore, who came from North Carolina in the ’40s “with a plan and a dream and anointed hands,” says Simmons. The deed for this lot’s purchase by Seymore in 1952—for the gasp-worthy price of $10—is a treasured item on display. Blacks buying property was unusual. A barber, he built this building. And Seymore was the last owner of this site as a barbershop. His grandchildren donated original business cards and the radio he used.

Simmons’ aunt Evelyn Baxter came from Virginia and settled in Harlem before she and Brenda’s mother came to Southampton. Baxter got her beautician license and was the first to work there, when a wall divided the space to create the beauty shop. As a teen, Brenda answered phones and made coffee runs to the local diner for her auntie’s beauty shop. And yes, some whites came too.

Brenda’s father, Noah Simmons, owned the Cottage Inn, a restaurant and juke joint, where, as kids, “we played on the stage, not knowing what was going on at night.” Aretha Franklin and James Brown passed through. “My dad gave the Lovin’ Spoonful their opportunity—some skinny white guys playing to an all-Black audience. How wonderful it was.”

Contiguous to the barber/beauty shop, Arthur “Fives” Robinson opened a popular juke joint. A vitrine of artifacts features shaving brushes, shears and hot combs from that era. Respected, barbers regarded themselves in an informal brotherhood that passed on knowledge and skills to younger men.

Exhibited downstairs is African American art from architect Peter Marino’s personal collection: works by Sanford Biggers, Kara Walker, Melvin Edwards, Glenn Ligon, Theaster Gates.

Most gratifying for Brenda Simmons is what SAAM can offer in this opportune moment, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death—“I call it a lynching: Our history is told the wrong way. I didn’t know the Hidden Figures story,” she says, referencing the popular movie, “or Tulsa,” or the occasion for commemorating Juneteenth, SAAM’s opening day. “Now is the time for us to tell our story properly. White people have to tell this story too.” saamuseum.org