When I attended college, I took a course called Great Books. The great literature then defined by the classics—American naturalists, German Romanticism, French philosophers and theorists—introduced me to the power of language and human identity. Thus began my thirst for analysis of literature, the relationship of words, their debate-worthy characteristics and their implications. What is considered literature today and how we study it is different than it was 30 years ago, and 30 years before that, and so on—but the collective impact of great books shapes our understanding of the world around us.

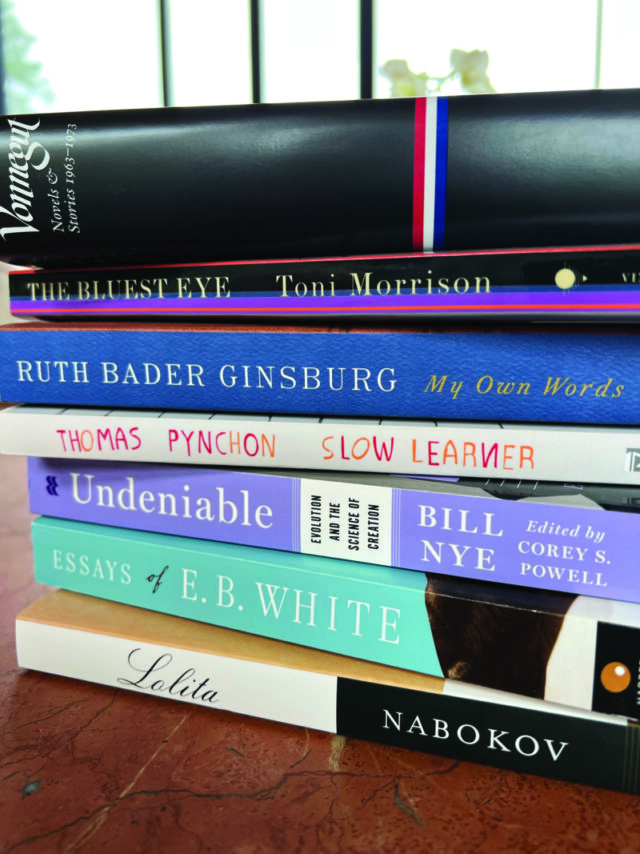

Since my eldest daughter enrolled in my alma mater, Cornell University, I took a renewed interest in authors who graduated from and/or taught at our university and created a summer reading list of great books reflecting how history, culture, literature, politics and technology have evolved. Perhaps you might find this bestseller list interesting too: Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s My Own Words, Toni Morrison’s Beloved and The Bluest Eye, Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and Slow Learner, Kurt Vonnegut’s Novels & Stories from 1963-1973, Essays of E.B. White (and for good measure, his Charlotte’s Web for my youngest), Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and Bill Nye the Science Guy’s Undeniable—Evolution and the Science of Creation.

Some of these deserve a second read. Lolita, for one, 30 years after I first read it, remains in a special class of satire, one that New Yorker critic Donald Malcolm described in 1958 as a “conjunction of a sense of humor with a sense of horror…It is the horrific rather than the comic aspect of the novel that has captured critical attention. This is not surprising, since Mr. Nabokov has coolly prodded one of the few remaining raw nerves of the 20th century”—referring to the monstrous affection of the protagonist toward child-girls, the same sexual deviation found in the mythology or poetry books that came before it. While writing this and other literary masterpieces at Cornell as a professor, Nabokov taught Russian literature rich in war and tyranny. In one of his inspiring lectures, he warned students against the enemies of art—banality, cliché and conformity: “I have tried to teach you to read books for the sake of their form, their visions, their art. I have tried to teach you to feel a shiver of artistic satisfaction.” This reading list will not only make one shudder at the artistic genius of the authors, but it will also inspire and ignite an understanding of where we are heading as a generation, rooted in rich history. For more great book ideas, check out the East Hampton Library’s 18th annual Authors Night, of which Purist is a proud sponsor, on August 13.

My conversation with our inspiring Purist cover subject sheds light on the direction in which we are headed. Liev Schreiber, of Ukrainian descent, has become a standard-bearer for the devotion to human welfare. He reminds us that, as Americans, we are at our best when we galvanize to protect the freedom of others, especially those in need as Ukrainians continue to defend themselves against that tyrannical Russian history, even though the news cycle has moved on to other subjects. In Schreiber’s words: “Our grandparents fought for these freedoms and liberties…There is strength in all of us, and there are values and principles that are worth standing up for.”