By Ray Rogers

Ray Rogers: In the body of work that comprises Icebergs and Suns, as in much of your previous works, you’ve found beauty in something that is quite terrifying. Tell us about that dichotomy.

Rob Reynolds: You’re tuning in to something that I think about a lot, beauty and the terrifying, the twin engines of so much great art through the ages. To my mind, I don’t really see it as a dichotomy—but as a more or less healthy, if sometimes troubled, conjugal relationship. Reading the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] climate report last week was, as you say, quite terrifying. We all have a lot of work to do; a question for me is what role can art play in it? Beauty and terror might have been the twin engines of many art historical movements, and seem to pop up in times of social upheaval and change. While fear of environmental collapse can be motivating, it can also be paralyzing. How to engage these issues is a big question. How we frame it is important. I hope my work brings forth feelings of possibility.

You’ve painted and made an incredible Carrara marble sculpture of an iceberg in Greenland that has since melted. Is this a way of memorializing the beauty of our planet—and showing people just what is being lost?

Yes, but also what is being gained through deeper awareness of our world and what can be done by not looking away. My original conception for this project was to make a new kind of monument of a rapidly disappearing planetary feature. That said, I try to remember that by melting, this iceberg did exactly what they have always done. It’s just that now—with the arctic warming a reported four times faster than the rest of the planet—it is rapidly accelerating, and awareness of this is changing the way that we view the natural world. Maybe much of the anxiety around this is that the language and the adaptation—our way of being in the world has yet to catch up with the knowledge of humankind as a geological force.

One of my curiosities is about scale, and a reason for working with marble is that on the most basic, visual level it bears an uncanny resemblance to glacial ice, and the second—that it has been used to make some of the most heartbreakingly beautiful works in the history of art, from Michelangelo’s Pietà to many others since at least the Renaissance. That it’s composed of sea creatures from roughly 200 million years ago adds another opportunity on geological time to trip out on. The iceberg sculptures do make me think of ghostly images and Renaissance death masks, but mostly I think of gongshi—or Chinese scholars’ rocks, prized for their shapes and their use for contemplation.

I loved making this sculpture and am making sculptures in this series of eight more actual icebergs, and also paintings, works on paper and some [augmented reality] installations. This project will be all-consuming for several more years.

Tell us about the immersive app that allows viewers a way into the iceberg sculpture. What was the thinking behind this?

What you are referring to is an AR lens that allows visitors to see a 3D-rendered, animated version of the iceberg in the gallery space. It is a relatively new platform and another tool in our artists toolbox, and I am using the Snap AR Lens Studio to make what I view as essentially prototypes. This aspect of the show is truly experimental and I am working with an engineer to place them in interesting places, as I did last night in Grand Central Terminal. It’s there and interested people can find it hovering over the information kiosk through my lens in Snapchat.

For this series you worked with technical image data captured by earth scientists studying icebergs and climate change. In what ways, for you, are art and science linked, and how has that informed your work?

For me the link is inseparable in this work—but there are some important but complementary distinctions. While Dave Sutherland of Oceans & Ice Lab [oceanice.org] and his brilliant team of earth scientists are creating technical images—iceberg geometries to understand melt rates and other features of calving on ocean currents and weather—I am interested in immersive art experiences. I hope to welcome people into the experiences and also want to open viewers to their scientific discoveries and the overall project of better understanding how the world works—a commitment to knowledge and enlightenment.

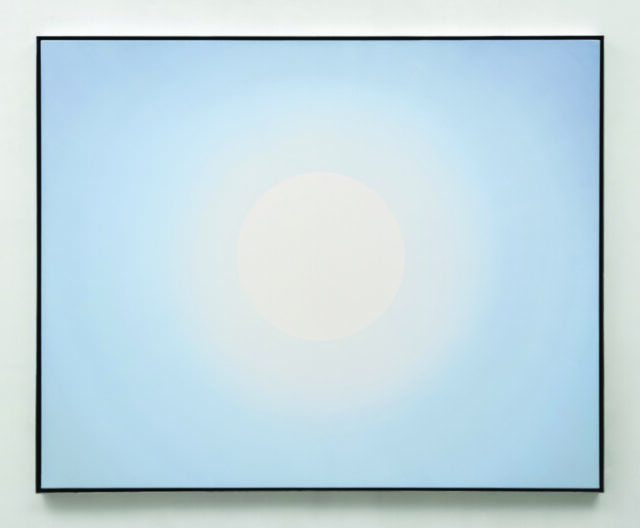

The title of the New Suns paintings makes reference to Octavia Butler’s famous line: “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” What do you find inspiring about this thought? What do you hope to give viewers a chance to reflect on in these works?

I am a fan of Octavia Butler’s sci-fi and poetry. She grew up in LA living right in Pasadena near the many California dreamers and visionaries that have shaped our world views—so she is also a local hero. There is just something about the world-weary and ultimately positive sentiment in this line that attracts me to it. For me the sun is one of the few things all beings can relate to—and it has so much of that same mix of beauty and terror you referred to earlier in our exchange. I feel that Butler’s line invites us to reflect on tomorrow, and what might be. But on the other hand, my sun paintings are also just circles in rectangles.

How can art help us better understand our world and our relationship to it?

Operating on a visual, experiential and intuitive level, I hope it might invite heightened awareness of our world and fill us with a sense of possibility.

A portion of proceeds go to support the Juneau Icefield Research Program. Why is it important for you to give back?

It just feels right for me. While the earth scientists were supported by the NSF [National Science Foundation] and other granting agencies, their work is an important part of my practice and I want to do whatever I can to support their research, share their findings and support long-term positive growth—winding down hydrocarbon production and consumption is going to be a long, complicated project. The Juneau Icefield Research Project is a perfect organization to support in kind. I love it because it is their mission to support diversity and recruit interested young people into the earth sciences. I also support Earthjustice—dollar for dollar, pound for pound, one of the most effective environmental organizations. I encourage everyone to look at both of these superb organizations and support them as well. mignoniart.com