Storytelling is the thread that connects time, people and past to present. One of our great storytellers is actor and director Kevin Costner. While his dominion over the ever-expanding Yellowstone universe was cemented this winter with the series airing on CBS, his passion project will be released this year, Horizon: An American Saga, a planned multipart series about the Western frontier that he co-wrote and directed. The megastar of Westerns—from Silverado to Yellowstone—and sports dramas like the epic Field of Dreams and Tin Cup, waxes poetic about The Dunbar, his Aspen ranch named after his Oscar-winning film Dances with Wolves’ character. From the 160 acres on the Great Continental Divide that he is tethered to, the outdoorsman shared stories about life on the ranch, his childhood, being a father of seven, and singing/guitar playing in his band Kevin Costner & Modern West. Here are just a few of them.

CRISTINA CUOMO: First question, before we get to chatting about the ranch. What has been your favorite role of all time?

KEVIN COSTNER: I’ve loved everything I’ve been able to do. I can’t nail it down to one, honestly. I could tell you Gardner Barnes in Fandango, or Frank Farmer in The Bodyguard. I could tell you Billy Chapel in For Love of the Game, or Charley Waite in Open Range. I loved playing the guy in Waterworld, and in A Perfect World. When people come up to me, they’re not usually talking about my role; they’re talking about their favorite movie. It revolves around nine or 10 movies. The biggest joy I get is that it doesn’t reduce itself to a single movie. I’m more pleased about that than anything.

CC: Tell me a little bit about The Dunbar, your Aspen home, and the life you like to lead there. How does nature direct your lifestyle?

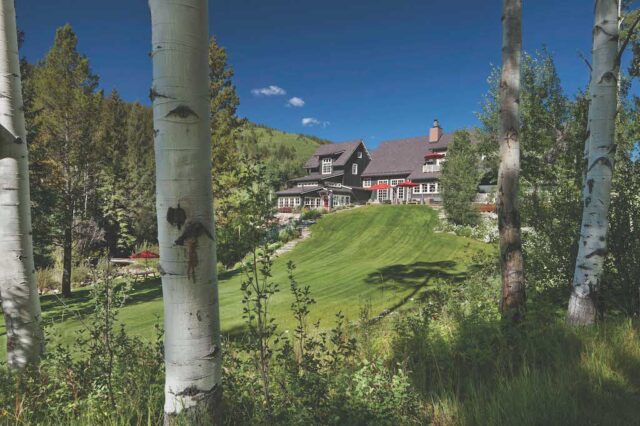

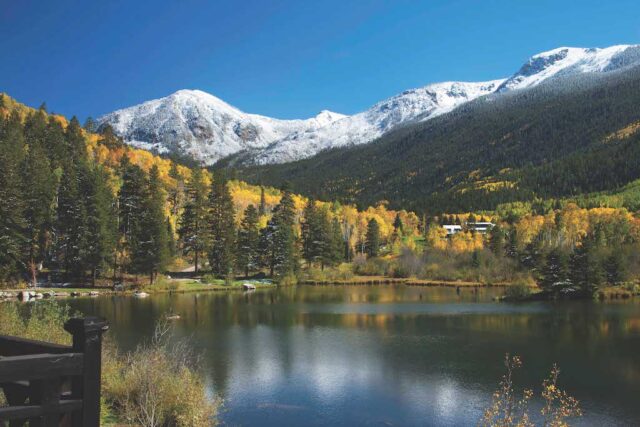

KC: I kind of dreamed of that place. My family didn’t have a lot of money, and so our vacations were going up to the High Sierras, camping with a Coleman stove, a canvas tent worn so old, that had been rained on so many times it had a familiar smell. I’ve never quite gotten over the scent, the way that the needles in the High Sierras are on the granite rocks, the way the sun bakes them and the wind blows. I’d always imagined I would have a place like that, but certainly I didn’t think I’d ever have the wherewithal to get one. I thought it was just going to be camping the rest of my life. But when I finally got to a point where I was looking, Aspen was just really not on the list. I wanted to be where I could hunt and fish, where I could be close to nature. I looked at many states. I had been going to Aspen as a result of having a deal with Warner Bros. They had a house in Aspen, and it was lovely. For about seven or eight years, I didn’t really get farther than the airport to that house. We would go in the winter to ski. I liked Aspen, but it wasn’t speaking out loud to me at first. One day, not going where everybody else went, I went the other way, over the Continental Divide. There’s a single highway that takes you to Twin Lakes through Leadville and then into Denver. I looked off to my right as the car was heading up, and I saw a flash of blue; I craned my neck as long as I could. While I was interested in seeing the Continental Divide, I was also really interested to look at this place on my way back. I got a different view of it, and wondered who owned it. I found who did, and negotiated for four years.

CC: That’s a long negotiation for land.

KC: It’s just hard for me to let go and get something out of my mind. I don’t fall out of love very easily. So, what happened was, I had one moment where I could buy it all, and there was a conversation. Somebody said, “Let’s just wait.” Eventually, I went back. I kept at it, and bought the first 35 acres, and then the other three-quarters came up for sale. I was in the midst of building a house called the Hill House. The land came for sale, and I went down to talk to the owner and said, “I will stop building. I will give you everything I own to buy this.” And he said, “No, I’ll just sell it to someone else,” which was kind of a cruel statement. He could have said, “This is my last chance and I’d love you to have this, but I’ve got to get as much out of it as I can.” My heart was kind of broken. And within two weeks, it came back to me, and I bought it. So now that valley is connected. When you roam there, you won’t be in danger of stepping across a line you shouldn’t. You can go wherever you want. From that moment on, I just began working there every year on my tractor and with my friends. There’s nothing that I didn’t touch and didn’t move. I’ve only started renting the place in the past six years. It was just for me and my friends, and they always asked me, “Aren’t you on vacation?” And I’d say, “I’m working. This is my vacation.”

CC: Your property is threading oceans. It’s quite magical.

KC: It can absorb a single family, or 500 people. The property takes what it has; the moose were completely gone in the Rockies, and then in 1975 they released 25 of them. Fifty years later, the moose made it over the hill. The first one came to my property, and now there’s a family of five. Bears hibernate on my property.

CC: What are your favorite rooms?

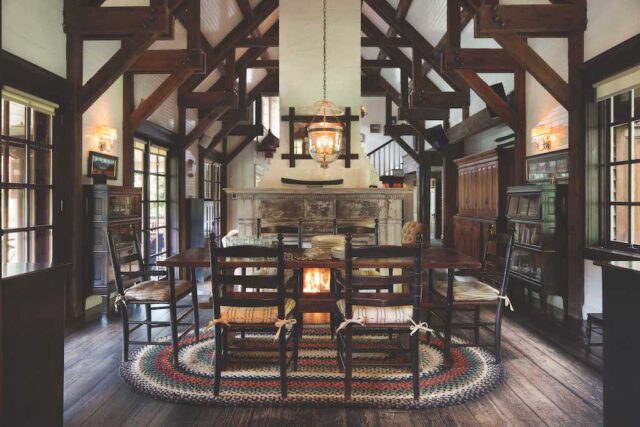

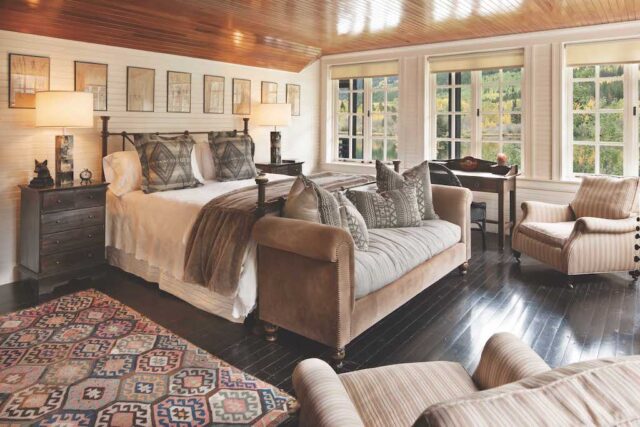

KC: The downstairs room in the Lake House is very magical, but I stay up above it because I love to have the doors open at night. The Hill House I fashioned after the CC Corps [Civilian Conservation Corps] when Roosevelt was putting men back to work, building trails and modest bridges. It was 12,000 square feet, and I built it with a metal shop, a barracks and a mess hall. It had all the trappings of 60 to 70 men living there every day going out with picks and shovels.

CC: What do you do to stay healthy in those great outdoors? Horseback riding, fly-fishing?

KC: I just make sure I get out. I start knocking on doors to see who wants to come with me. Look, I’m guilty. I’m vain. I want to live forever, because I just love what I’ve been able to do, and it’s not that I haven’t been bruised in life. I have. But I still love the chances, and the opportunity, and more importantly, I share that place. There are children now who were going there when they were a year old, who now have their own children. My children have learned how to share it. That was probably the big lesson for me to give them, which is, we don’t throw a wall up around our good luck. We find a way to share this special place. I designed it for fifth graders; it’s like you get to be Huckleberry Finn. We plant trees and we paint fences. Even the guests have to do it, at least when I’m there. I tell them, “When you come back, you’ll remember that you planted that tree, that you painted that fence.”

CC: Where do you feel most tethered?

KC: The outdoors has its own clock. We’re always trying to think about what to do, and how to negotiate our time in a city. When you’re outside, if it’s cold, you put a jacket on. If it’s dark, you turn on a lamp. If you think you’re going to run out of firewood, you have to go get more. The outdoors talks to you. When you’re hungry, you make something to eat. You don’t have a 1 p.m. lunch in the mountains. You eat when you can. I like the rhythms of nature telling me what to do.

CC: Does that same intuition direct you toward specific projects that relate to your lifestyle?

KC: I don’t try to do anything that relates to my lifestyle. If I did, I wouldn’t have made JFK or Thirteen Days. I don’t like how I look in a suit. I don’t feel right. I know that’s awful.

CC: It’s not awful. I just think people would beg to differ.

KC: I was kind of traumatized wearing suits. We used to go to Sunday school and my dad said, “You cannot play, Kevin.” I just had one set of Sunday school clothes. It was in Compton [California], and I got out of church and all I wanted to do was play. Inevitably, the shirt would be out of my pants. I was just having fun, and around the corner would come my father and he’d look at me, and I thought, “He said not to play.” I always remembered suits just felt better when the shirt was outside, because that’s where it ended up when I’d play. I always felt like my clothes just hung on me, and I keep thinking my stuff just hangs on me. I go back to being 6 years old, and being in trouble. With a suit I always got in trouble.

CC: Can you talk about your upcoming two-part epic Western movie project, Horizon: An American Saga?

KC: I started thinking about it in 1988; I tried to make it in 2003-2004, right after Open Range. The studio wouldn’t make it. I waited another six or seven years, and decided to rework the first one and reengineer it. I’ve started thinking about Westerns the way I’ve grown up with them, the way I liked them. It’s hard to do it well. It’s really easy to do it badly. That’s why there are not a lot of great Westerns, because they’re hard to make. This guy coming into town usually has a skill set that he’s trying to leave behind. He comes into a town that’s fully formed, and he wants to stay there, but he has to resurrect the set of skills that he’s left behind. Of course, that leads to the action, to violence, to trying to make things right.

When it’s done well, we’re thrilled by it, but more often than not it’s just too simple, too convenient. It wasn’t simple back then. It was difficult. They had to make hard choices. It’s not unlike today. Money ruled the day. I wanted to take this person that came off the horizon that we don’t know anything about, and I wanted to take this town that suddenly was already there, like some magic mushroom that popped up. I thought, what if we know a lot about the guy coming off the horizon? What if we know a lot about this town? What if we saw the town built? I wanted to debunk the truth about how towns came to be, and so I took a script that was written in 1988 and started working on it with Jon Baird. We wrote four of them. It turned into a saga about how these towns came to be. One day, I’ll make the original from 1988. What we have now is four scripts taking us through the beginnings. It’s a journey, and it’s very heavy with women.

CC: Oh, that’s good.

KC: They’re interesting and they’re tough. They’ve worked themselves to death just keeping their families clean, a 24-hour job. They were often dragged out there, not of their own doing. So, I deal with that. I’m in love with that stuff.

CC: Will you direct it?

KC: I’ve directed two of them. I finished the first one two nights ago, and I’m editing the second one.

CC: Congratulations.

KC: Hopefully, I’ll make the other two next year. The goal is to have them come out every four to six months, so that you fall in love with the story, you want to follow the characters, you believe in the story. I always do things backward. People make a movie and say, “Oh it’s kind of popular, let’s make another one,” and two years later it comes out. Me, I’m kind of a nut. I just said I kind of like these stories the way they are. I’m just going to make all four of them. Conventional wisdom comes at me and says yeah, but what if they don’t like the first one. I said I still have to make all four of these. My job is to try to just make this, put it out there, let people go sit in the dark and make up their own mind.

CC: Tell me how you got into music, and forming your band, Modern West.

KC: That just came out of being in the church, and my grandmother, mom and aunt being in the choir. I’ve trained classically on piano, and then growing up during the whole wave of the ’60s, I was 14 or 15 when the music scene was turning left and right, up and down. Vietnam was going on. I had a band early in my 20s, and then I let it go, because the movies were starting to take hold of me. I came back to music probably over 20 years ago, when I called up John Coinman and said, “Look what we started; do you want to pick it back up again?” I would like to write original music and play wherever I’m happening to make a movie. That was the only goal, just to play in the community where I was working, do something that couldn’t be interrupted by a selfie or an autograph. Once I was on, nobody could stop it, except me.

CC: What deserves your hard-earned respect?

KC: I like people who are careful with my time, careful with my feelings. I respect that. I like people to be careful around me, because I’m open to them and they can misinterpret that. It doesn’t mean I can be taken advantage of. I just try to be open.

CC: You love storytelling.

KC: The days are so long when you direct, but Horizon would never look the way it looks if it was in someone else’s hands. The architecture of everything I do is built on an idea that you will see something that you’ll never forget. A look, a kiss, a word, a phrase. Something that hurt you, something that thrilled you. That’s when cinema is working at its very best.