Waking up on one of the world’s best-known regenerative farms is a unique sensory experience. First, the sounds: an eerie cacophony of the bellows of thousands of cattle floating on the mist that has transpired on the knee-high pasture outside my guest cabin. Then, the touch of dew-soaked pants on my skin from a pre-coffee amble, as the carpet of cattle fodder transfers its humidity to my skin. But most of all, the sight of green upon green, so many hues even a professional writer’s words fail to do it justice. This is what a farm that works with nature, not against it, looks like in the coastal plains of southwest Georgia.

It’s exciting to get this intimate with farm life. Up close with the herds of cattle that have just moved, en masse, from one paddock to the next—sections of farm are divided up like a checkerboard so the herds briefly impact one quadrant of land at a time, helping the deep-rooted perennial grasses grow—it feels like normal time has dissolved. The river of sleek-coated, majestic animals looks primal and prehistoric as it moves across the emerald pasture with egrets the color of toasted marshmallows darting above it, a sign of ecological health. Hours later, flocks of chickens, pecking at the earth for grubs, catch the golden light with their feathers like movie stars at Cabo before retreating into their movable houses for the night, shaggy guardian dogs patrolling the edges of their terrain. During a torrential rainstorm—I am quite certain it’s a Category 5, but Will Harris III, the farm’s owner, calls it “a good rain”—a mama goat shelters her baby under hedgerows, just fine with the elements despite my nervous misgivings. Life with its constant turning of growth, death, decay and regrowth is everywhere. It’s a very different picture from neighboring fields, where intensive row-crop farming using tillage and chemicals have left expanses of terra-cotta-colored subsoil exposed and baking in the brutal sun. Harris likes to talk about nature and the cycles that drive its abundance. Humans have tried to tamper with nature, to improve it, manipulate and better it in the quest for cheaper, faster food. But we are nothing, really, compared to its awesome force. Nature always bats last.

the split between land and livestock” that industrial farming created.

I came to White Oak Pastures, a sixth-generation operation (if you count the grandkids) that raises 10 species of meat and poultry on pasture and has become a beacon of the independent small-food movement, drawn by a personal epiphany that only the soil will save us. Documentaries and podcasts have awoken me to the fact that healthy grasslands draw carbon out of the atmosphere and lock it in the soil via plants and their roots, and that livestock raised in ways that emulate how our ecosystems evolved over time—with herds of ruminants moving actively across the land, trampling plants and manure into Earth’s surface as they go—help this carbon cycle to function. I’ve learned that profuse vegetation and trees help the Earth’s water cycle to work—a vital piece of the planet’s temperature regulation that is breaking drastically the more we clear land for vast swathes of monoculture crops and miles of concrete sprawl, thereby contributing to superstorms and wildfires. And that the multiverse of microbes living in vital, intact soils make our food more mineralized, and consequently build our health. Light bulbs have gone off for me in what feels like a foreboding moment of planetary collapse and I want to throw my weight behind a different kind of food production. Besides, my family and I like eating meat, but we can’t endorse misery meat raised cruelly in industrial confinement facilities. So I traveled 2,300 miles to the tiny hamlet of Bluffton, Georgia, to see how a de-industrialized farm does it, one who (very unusual today) oversees each animal through its entire life cycle and whose credo is to let livestock express instinctive behaviors every damn day.

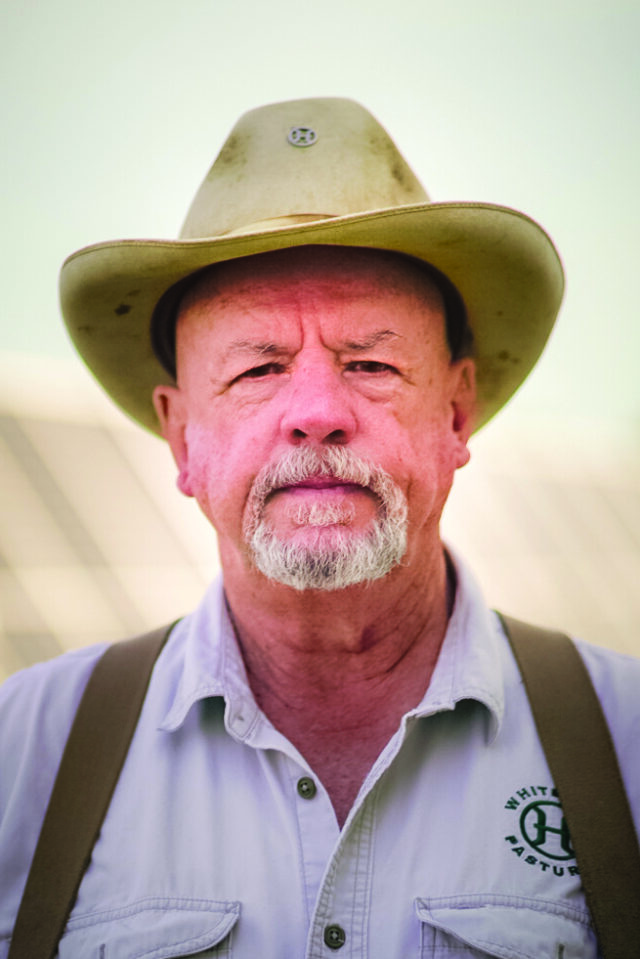

The farm’s origin story is, to carnivore-oriented foodies and fans of better farming, quite well known. Its owner, Harris, tells it often these days. Harris is the OG of regenerative agriculture; he began reversing the damage that intensive modern agriculture has wrought long before “regen ag” had the buzz (or even the name) it has today. And he says that for years, no one cared much about the tale of a former industrial cattle rancher in an overlooked corner of rural America that bet the farm on returning to the simpler, more self-reliant methods of his forefathers.

It was a journey that started roughly 25 years ago when he got disgusted by the excesses of modern cattle-raising, with its unnatural diet of grains, on-tap pharmaceutical drugs and crowded feedlots that turned cows into obese, sedentary creatures dying of diseases of civilization. He began striking out on what he calls a “radically traditional” path of raising fully grass-fed beef—a real oddity back then.

The path led him, over time, to regenerate acres of depleted land, add multiple species to the mix like his grandfather had, and restore animal welfare to what is arguably a near-utopian existence. And because Harris had the audacity—he just calls it the balls—to build his own meatpacking plant and later, a fulfillment center, each requiring a significant workforce, it’s also revived a forgotten American farm town that the centralized meatpacking system had rendered obsolete. A hundred- plus years ago, White Oak Pastures slaughtered and butchered everything on-site; most farms worked that way. But in reclaiming that critical piece of food production, it’s the definite outlier today.

Somewhere during my farm-stay sojourn, all the inquiries I arrived with about the problems of glysophate and how soil fungi work dissolve away. In their place is a more holistic feeling of rightness, things working as they should. There’s the land (which an analysis showed stores more carbon in its soil than the grass-fed cattle emit; this means the soil is keeping carbon from the atmosphere), and there are the animals, lots of them, and there are the people involved in producing the food too. Not just the herdsmen and women outdoors, but the guys working the kill floor of the non-mechanized slaughterhouse and separating carcasses in the chilly cutting room, where loud music plays to keep everyone loose and warmed up. (This is a farm with no secrets; visitors can see every part of production because transparency is their sword in the fight to teach what food raised the right way is really like.) And the folks who drive the trucks transporting any remains not used for food, or dried pet chews, or tallow skin care or cowhide home decor (the farm produces and sells all those things) to giant compost piles, where a year of maturation makes what conventional operations would deem waste into a superb nutrient stream for the pastures, feeding the soil so the cycle of life starts again. We so easily forget that other humans work hard to get our food from farm to fork: people just like us with stories and families and dreams of their own. We don’t usually see or meet them, but we should.

As news of food shortages, and agricultural droughts, and grocery price-gouging fill the headlines, the world “out there” feels unsettlingly rocky. Here at this hub, which Jenni Harris, Will’s middle daughter, laughingly calls “a shiny little rhinestone in the Bible Belt,” you’d almost forget. White Oak Pastures pioneered the “regenerative” genre but the Harrises barely use the word now. That’s a given. They talk mainly about “resiliency” today. They produce meat (and vegetables, eggs and honey) from the sun, water, microbes, minerals and manure they already have—no fertilizer or expensive industrial inputs required— and they turn everything they raise into food themselves, selling much of it directly online, no outside plants or middlemen involved. They’ve also rebuilt a bustling rural village with uncommonly young farmers living in it, a pleasing side effect Harris never predicted. Even while circling back to the farm’s roots, the Harrises stayed ahead of the curve. And that feels right too. As I dig into a delicious meal at their simple farm-to-table restaurant, I think I just might have to stay awhile.

Cabins from $110 per night; whiteoakpastures.com